7 Greek Plays You Need To Read

And how they'll change your life...

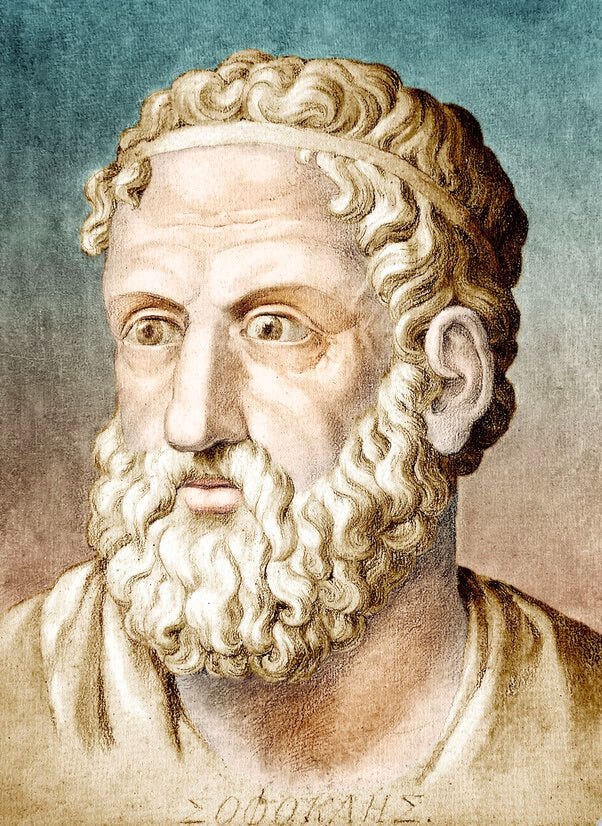

Aeschylus is “the Father of Tragedy.” He was an ancient Greek playwright who wrote a prolific 80 plays in his lifetime. Athens adored him as a genius dramatist, and his talents were richly rewarded at literary competitions.

That said, his stories were far more than popular entertainment, rather they became the intellectual bedrock of Greek Antiquity. His plays gave Athens a nascent understanding of justice, truth, and virtue, and inspired the likes of Plato, Aristotle, and Socrates, effectively founding the beginnings of Western Philosophy.

Tragically, only 7 of his plays survive to this day, but they are masterpieces that will help you understand Greek Antiquity, the roots of your intellectual heritage, and the beginnings of the philosophic quest to “know thyself.”

Reminder:

I offer one on one coaching for men, focusing on faith, fitness, and the Great Books. More info here.

Additionally, if you’d like to support my mission of restoring Truth, Beauty, and Goodness to the West, subscribe below!

1. Prometheus Bound

This is my personal favorite of Aeschylus’ surviving plays. It dramatizes the punishment of Prometheus — the Titan who defied Zeus and gave fire to mankind. As a result, mankind grasped the means to build civilization, but Prometheus was given a grueling punishment:

He was chained to a rock, and tormented by an eagle who consumed his liver daily, only for it to regrow so that Prometheus could endure the same torture the next day.

The play features static dialogues between Prometheus and his many visitors. The titan mourns his punishment, which he finds too much to bear, yet finds solace in a prophecy of Zeus’ foretold doom, which he refuses to share.

At the heart of this play is a portrayal of literature’s first anti-hero — Prometheus defies the divine order both for pride, and for love of mankind. He’s a rebel against God, yet a savior of mankind, and the reader is left to deduce whether Prometheus is a just “giver of light,” or a demon of Hades.

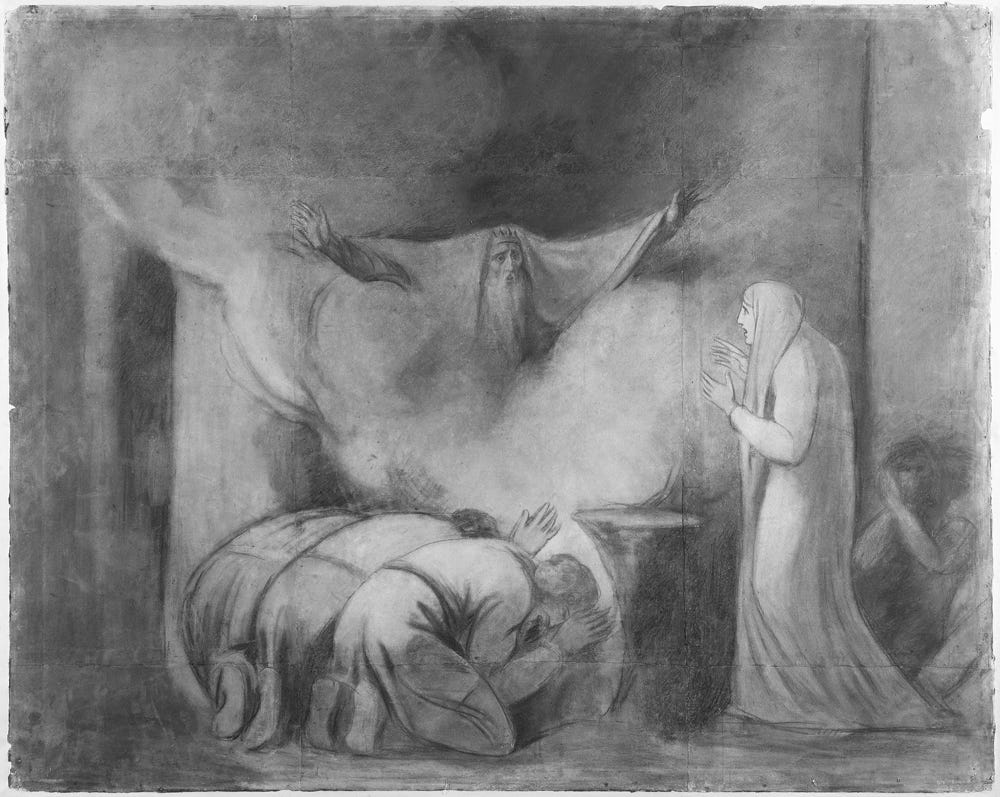

2. The Persians

The Persians is notable for its empathy. This play tracks King Xerxes and the lament of Persia’s downfall after losing its war against the Greeks. This play is remarkable, because Aeschylus was a soldier who fought the Persians at Salamis. In a world where national pride and tribal warfare reigned, he defied norms by humanizing his greatest enemy, who was also a world superpower.

This play not only dramatizes the sobering reality of defeat, and its accompanying despair, but is also one of the first texts in history that humanizes “the other,” — a play that helped mankind’s intellect rise above the “eye for eye,” justice of tribal warfare.

3. Seven Against Thebes

This play underscores the tension between divine will and human agency. The Greek world was highly fatalistic, an era where mankind believed their lives were subject to the fickle twists of fortune, fate, and the gods.

At the same time, Athens began to garner an identity as a self-governing city-state, undergirded by democracy. Its citizens discerned a personal duty to embrace law and order, as opposed to earlier codes of ethics that favored martial prowess and personal gain without consideration of one’s community.

In the play, Eteocles, king of Thebes, is battling against a curse against his city as decreed by the gods. His doomed struggle for virtue suggests that Aeschylus views the polis as man’s moral maturation, that mankind doesn’t find his identity in personal glory, but through relationship to his community at large. The aim of life was not immortal glory on the battlefield, but civic virtue that serves the good of your city and neighbor.

4. The Suppliants

The Suppliants is the first play of a tetralogy, though its sequels are lost today. The play stands strong on its own, however, and continues exploring Aeschylus’ theme of the polis as mankind’s moral maturation.

The play follows The Danaids — 50 daughters of Danaus who are fleeing from forced marriages in Egypt. They arrive at the doorstep of King Pelasgus of Argos, imploring his protection.

The King refuses to make a decision on his own, but consults the people of Argos to make a decision for him. It’s a decidedly democratic move that pays homage to Athens’ growing democracy, and impresses Aeschylus’ belief that justice reigns through the wisdom of the crowd, rather than singular individuals.

5-7 The Oresteia

The Oresteia is Aeschylus’ masterpiece. It’s the only surviving trilogy of any of the Greek playwrights.

It follows protagonist Orestes, who is caught in a precarious situation. His mother, Clytemenstra, murdered his father, King Agamemnon, who had recently returned from the Trojan War.

The gods call on Orestes to avenge his Father, but to do so would incur the wrath of the furies, primordial beings of chaos who torment slayers of kin.

The story ends with an immaculate trial, overseen by Athena, goddess of wisdom, and a jury of Athenians. The play gave Greeks an understanding of divine authority and its relationship to justice — that true justice lies beyond human reach, yet can be discerned through contested dialectic within a court of peers, ordered toward the divine.

Effectively, rather than denying human responsibility, Aeschylus dramatizes humanity’s movement from personal vengeance to communal institutions capable of adjudicating justice. Once again, he pays reverence to Athens, marveling at the polis as man’s maturation out of tribal warfare into a nascent civilization grounded in law, order, and justice — fertile ground for the birth of Socratic philosophy.

Conclusion

Aeschylus is rightly enshrined as a father of the West’s literary tradition. His plays are an intellectual bridge between Homer and Socrates, which also provide us a glimpse into the heart and soul of Greek Antiquity.

It was these narratives that taught ancient man to look to the divine. To ascend beyond the bloodied tribal warfare of the Bronze Age, it began with playwrights and poets dramatizing stories that asked the simplest questions — What is the nature of man’s free will in accordance with fate? What is his relationship to the gods? What is the good life?

On the other side of such questions was the birth of “the great conversation,” and the discovery of everlasting virtue.

Thank you for reading!

If you’d like to go deeper:

I offer one-on-one coaching for men on faith, fitness, and the Great Books. More info here.

Subscribe for free to receive weekly emails exploring the Great Books and their lessons on Truth, Beauty, and Goodness.

Paid members get an additional members-only email each week!

Omg! I loved this, is amazing.✨

What I love is that they are theatre, and quite like a musical at that. The very word “chorus” is based on the form the chanters took. And in fact they were the popular works of the day, usually performed in all-day competitions. Nothing obscure to these audiences, these were offerings to the gods.