Faust, the Devil, and Why Modern Life Feels Empty

Why Striving Alone Can’t Fill the Void in Your Soul

Goethe’s Faust is a masterpiece — a classic “deal with the Devil” tale about a man who sells his soul for worldly gain… but this play comes with a twist.

This isn’t your typical Christian story about resisting temptation; it’s actually an allegory of the spiritual crisis of modern man. Goethe saw a modern world skeptical of religion yet carrying a “God-shaped hole” in its heart.

His life’s mission was to show how man could live a meaningful life without traditional religion, and Faust was his grand attempt at a solution. This work is brilliant, ambitious, and intellectually rich — but ironically, it falls short.

Yet it's the very shortcomings of Faust that make the play brilliant — it exposes the hidden temptation that has ruined the heart and soul of modern man, teaching us that it’s far easier to “sell your soul,” than you’d think.

Here’s the story, and what it reveals about the modern day devil — and the true answer to living with meaning today.

Reminder:

Subscribe to support my mission of restoring Truth, Beauty, Goodness, and God to the heart of the West!

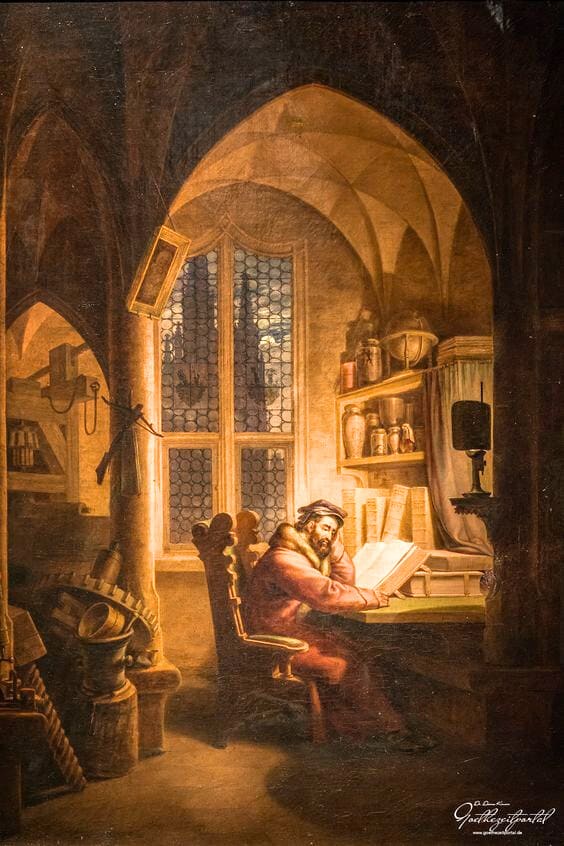

The Futility of Knowledge

The play follows Dr. Faust. He’s an educated scholar who’s grown dissatisfied with the world. He laments that though he’s studied “everything,” he remains unhappy. No amount of book learning, he concludes, can bring him peace.

In this disillusionment, he gets a visit by a devil from hell:

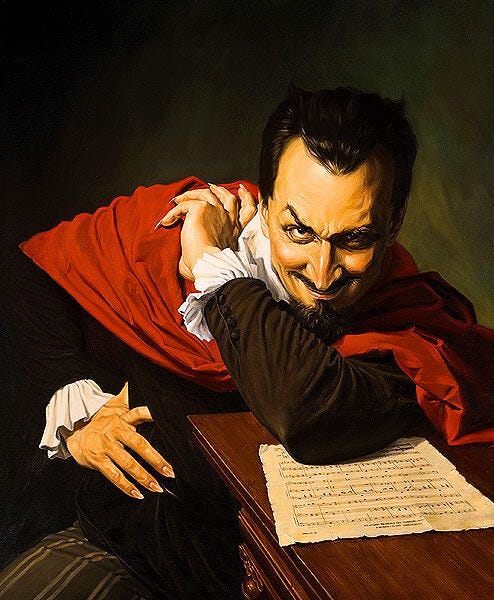

Mephistopheles.

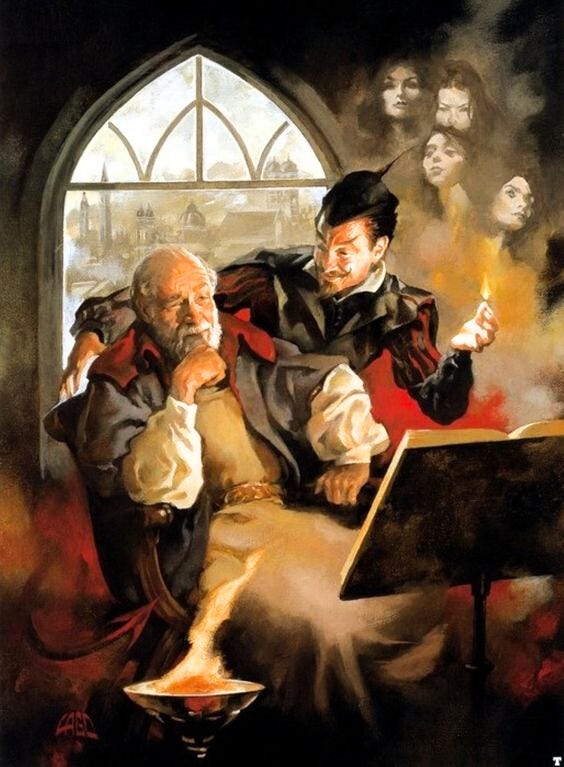

The Demon comes with a simple but familiar promise — sign this contract, and I’ll give you all the powers of hell to do your bidding.

The catch?

If Faust ever finds true happiness, Mephistopheles will snatch his soul for eternity.

Faust, the over-ambitious, dissatisfied, and skeptical scholar, signs on the dotted line.

To what heights will his ambition take him?

Pleasure, Pleasure, Pleasure

With all the powers of Hell at his disposal, Faust’s first schemes are, surprisingly, pathetic.

He doesn’t inquire with Mephistopheles about divine knowledge, nor dare to see the heavenly realms of the cosmos. Instead, he rejects knowledge altogether.

He instead seeks happiness in worldly pleasure, of all things.

With Mephistopheles’ power, he enjoys riches, food, drink, and all the delights that sensual pleasure can grant him. He even begins a tragic affair with a woman named Gretchen — but impregnates and abandons her, to her shame.

The affair ends in tragedy, with Faust lamenting that neither book-knowledge, nor worldly pleasure can save him.

From here, he turns to greater ambitions, unlocking the full potential of the demonic.

Mysticism, Power, and Beauty

Rejecting the modern world, Faust turns to mysticism.

He visits the ancient Greek mythological world and marries Helen of Troy — the most beautiful woman in existence. This is not just another attempt at romance, rather Faust hopes through Helen to discover the ultimate Beauty of reality. He wonders if Beauty incarnate is happiness.

This too, ends in failure, and Faust discovers that neither philosophy, sublime beauty, nor even the grandeur of the ancient mythological world can satiate his soul.

The play ends with a last ditch effort at politics — hoping power could satisfy Faust — but predictably this too ends in failure. Throughout the duration of his life, Faust remained unhappy and miserable…

The play’s ending has a deus ex machina — God saves Faust through an act of mercy — but the play’s genius lies not in the happy ending… this play is so masterful precisely because Faust lived, and essentially died, in despair.

Despite the Christian imagery that Goethe uses, this is not a Christian play. In fact, Goethe himself rejected orthodox Christianity and all organized religion.

And it is precisely this rejection that explains Faust’s despair. To see why, we must return to the beginning, where one crucial mistake set the course of his misery.

A Fatal Mistranslation

We first met Faust in his study, lamenting that book knowledge could not make him happy. But there’s an easy-to-miss detail.

He was translating the Bible — and mistranslated a key passage, John 1:1, which traditionally reads:

“In the beginning was the Word.”

The original Greek “Word” is Logos — divine order, the intelligence of reality, natural law, and the guide to living a good life. Traditionally, this meant true life is found by knowing and loving the Logos.

Faust, however, renders it differently:

“In the beginning was the deed.”

That single line explains the entirety of his misery.

Faust is unhappy because he lives in a world without Logos. No truth, no good, no evil — and therefore no ultimate meaning.

Instead of Logos, life becomes mere action. For Faust (and Goethe himself), meaning is not discovered but created — through striving.

Thus Goethe suggests Faust’s life is “meaningful” only because he strove, even in unhappiness. In this view, a world without religion is a world without truth, good, or evil. There is no “good” life, only a life to be lived — filled as fully as possible through creative action.

This is the heart of Faust’s despair, and of modern man’s spiritual crisis: life reduced to meaningless action, an endless striving meant only to distract from the misery of being.

Such a worldview has dire consequences — but also hints at the true solution.

Conclusion

The dire consequences of Faust’s philosophy are clear. His life is morally gray, even condemnable — yet cannot be called “evil,” for he denies evil exists.

Thus his atrocities — ruining Gretchen, or causing the death of innocents — are dismissed as mere “errors in judgment,” not true wrongs. In such a world, “anything is permitted.” Yet even unlimited freedom leaves Faust miserable.

The solution, though not offered by the play, lies in correcting Faust’s mistranslation:

“In the beginning was the deed.”

Faust must rediscover that the Word — the Logos — exists. Goethe shows that life without good, evil, and Truth collapses into despair. Like Faust, modern man may chase wealth, sex, power, or pleasure, but all roads end the same: an unsatisfied life and dread of death.

To rediscover the Logos is to embrace humility — to admit that life is not about personal happiness but about loving Truth. It means acknowledging that Truth exists, is greater than us, and demands our submission.

The paradox is that only in such submission — the forgetfulness of one’s happiness — can true happiness be found. For modern man to find himself, he must lose himself. His motto is not to embrace “the deed,” nor to “live his truth,” but to love the Truth.

This love is stubbornly ancient, yet it alone promises not just happiness, but a hopeful, meaningful future.

Thank you for reading!

Subscribe for free if you would like weekly emails on the Great Books, and their life lessons on Truth, Beauty, and Goodness

And remember:

Paid members receive an additional members only email every week!

This was a very interesting article! Not having read the play myself, I’m wondering if it gives us clues as to WHY Goethe rejects religion?

Ah the “Faustian Bargain” still exists in this world. Good essay here.