How to Grieve Without Losing God

Tolkien’s Forgotten Source of Hope in the Face of Death

How can a good God let you suffer and die?

Tolkien said a 600 year old poem titled Pearl had the answer to this question. Tolkien himself was no stranger to death — he was orphaned by age 12, and later lost his friends in the trenches of World War I. If anyone was qualified to give advice on overcoming human misery it was him.

And if we’re to believe Tolkien, this obscure medieval poem won’t just give us solace, but provides the means to persevere through poverty, pain, and heartbreak and live meaningfully.

Here then is the genius of Pearl through the eyes of Tolkien, and what it can teach you about God, grief, and finding hope in the face of death.

Reminder:

Subscribe to support my mission of restoring Truth, Beauty, Goodness, and God to the heart of the West by subscribing!

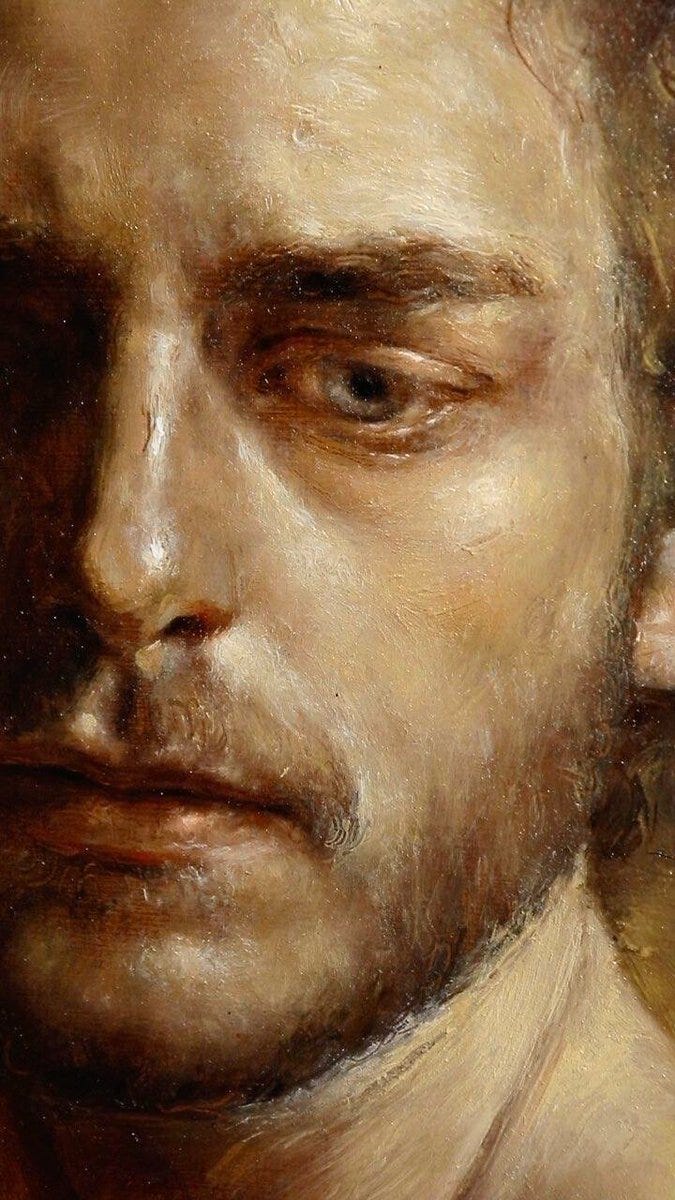

A Father’s Agony

The plot of Pearl is quite simple. Its protagonist is an unnamed Father grieving the death of his two year old daughter, named Pearl.

His grief is so all consuming it threatens to become despair — a spiritual renunciation of faith in life’s goodness. Such despair puts his soul in grave danger, but hope is not lost. The Father falls into a deep sleep, and encounters a dream that will prove life-saving and providential.

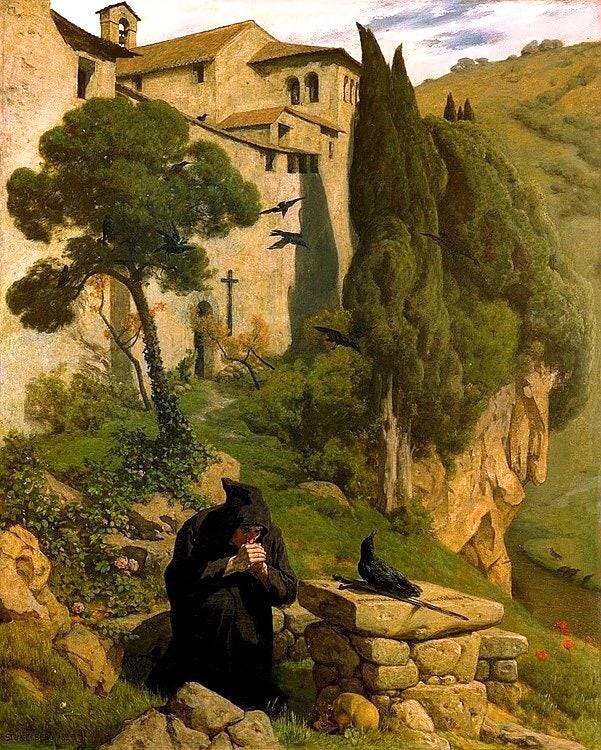

In this dream, the Father arrives at a paradisal garden. It’s filled with lush grass, tranquil streams, beautiful scenery and vegetation. More importantly, the father himself feels at peace. Though this is a strange new land to him, his heart swells as if this is the home he’s always longed for.

In this dreamy paradise, the father remembers Pearl, but her memory is now dear to him. This already hints that the Father is not in an Earthly Paradise — one with material joys to numb your pain — rather he’s in a Heavenly Paradise, where his sufferings are transformed into joyous and tender memories. Yet the Father will learn this lush garden is more than just a dream-world of joy.

He ventures deeper into this garden, and from across the stream he sees an appearance that makes his heart stop:

He comes face to face with a beautiful, full-grown woman, whose beauty surpasses anything he’s encountered on Earth.

Stunningly, however, he knows exactly who this full grown woman is:

His deceased child, Pearl.

Her face is radiant and full of light, and the father's spirit bursts with heart-wrenching joy. He couldn’t be happier to reunite with his daughter, though Pearl’s first words will prove… quite surprising.

A Daughter’s Correction

First, the Father expresses the agonies he suffers back on Earth, separated from his daughter. He’s grateful she’s alive and well in paradise, but wishes he could bring her back to Earth.

Pearl, however, says her Father’s intentions are impure, and his conception of grief is based on a lie:

"You tell your tale with wrong intent,

Thinking your pearl gone quite away…

Methinks thou dost thy mind abuse,

Bewildered by a fantasy;

Thou hast lost nothing save a rose

That flowered and failed by life's decree:

Because the coffer did round it close,

A precious pearl it came to be.

A thief thou hast dubbed thy destiny

That something for nothing gives thee, sir;

Thou blamest thy sorrow's remedy,

Thou art no grateful jeweler."

Why does Pearl call her father ungrateful?

She first emphasizes he’s lost nothing — his daughter is in heavenly paradise, and he’s promised a reunion if he lives with faith. Yet here’s where the poem gets interesting:

Pearl gently rebukes her Father — he’s let his tender grief fester into despair.

Grief itself is normal, natural, and good, but to despair and give up on life is to commit a grave mistake. Ironically, it’s only a renunciation of faith that can separate Pearl from her father. The father needs penance, and his suffering is meant to correct his disordered, possessive attachment for his daughter.

So what does virtuous love look like?

Pearl will explain the love that will save her Father’s soul.

A Life-Saving Love

After his scolding, the Father sees the error of his ways and repents.

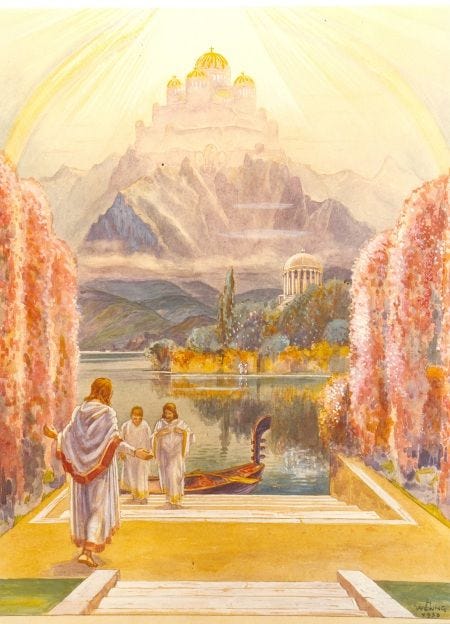

Pearl reminds him this vision is a mere dream — soon he’ll return to reality with his pains — but Pearl won’t let him leave without a parting gift. Her gift is a vision of Heaven itself:

The Father sees an image of the New Jerusalem. It’s a paradisal city filled with Saints and the Lamb of God.

The joy becomes too much for him to bear, and he rushes forward, eager to grasp Pearl and return with her to this heavenly city. Though as he dives headlong into the stream he wakes back up into reality. The horrid aches of grief return, but his dream was not in vain. In the concluding lines, the father states:

“Where my pearl to the grass once strayed.

I stretched my body, frightened, chill,

And, sighing, to myself I said:

‘Now all be to the Prince's will.’”

The Father’s pain is strong as ever, but his despair is defeated. From this day forward, he vows to live life and carry his cross, no matter how bad the pain.

Conclusion

What Tolkien saw in Pearl was not a poem that ends your heartbreak. Instead, Pearl is the poem that teaches you strength to grasp in the middle of heartbreak. Suffering is a guarantee in life. The “good news,” is not an easy life, but the grace to endure any difficulty.

Here’s Tolkien in his own words:

"The poem is a profound meditation on the paradoxes of faith:

the loss that leads to gain, the sorrow that yields joy, and the justice that is reconciled with mercy in the divine economy…

The grief of the narrator is deeply human, yet it is answered by a divine joy that transcends mortal understanding. In this tension lies the poem’s power — a reflection of the Christian hope that in loss, we find ultimate gain. The journey of the narrator is not a descent into despair but an ascent into understanding.

From grief to grace, his path reflects the transformative power of divine revelation, turning personal loss into eternal gain.”

The Father despaired because his love for Pearl was possessive.

He was too attached to Pearl, such that he even wished to deprive her of heavenly glory if it meant he could have her back. The vision of Heaven healed him, because it reoriented his heart to God.

It’s the same moral as the Book of Job — God does not answer all questions, nor end all suffering — but his presence brings grace and joy that cut through worldly agonies.

Only once the Father learned a true desire for Heaven could he let Pearl go, and only by letting Pearl go did he grasp the faith to bring him back to her.

The answer to grief and death then, is memory of the cross itself. The Christian promise is not that suffering ends, rather one draws from the face who conquers death itself. Pain is but a pointer to heavenly glory, and a true desire for heaven heals the soul to nobly pursue Truth, Beauty, and Goodness, even in a vale of tears, for in the end, eternal paradise is the promise.

Thank you for reading!

Subscribe for free if you would like weekly emails on the Great Books, and their life lessons on Truth, Beauty, and Goodness

And remember:

Paid members receive an additional members only email every week!