Lust, Empire, and the Life Lessons of the Aeneid

How Lust can destroy a Life, and an Entire Kingdom

Virgil’s Aeneid is one of the most influential poems in human history. It’s the founding myth of the Roman Empire and the narrative from which all great empires of the West draw, including those of Charlemagne and Great Britain.

In other words, this poem gave an entire empire its identity, and provided the blueprint for subsequent empires to rise from the ashes and flourish.

But while the Aeneid is famous as a founding poem, it is perhaps equally notorious for its romantic affair. It reveals how — of the myriad of dangers that can befall a soul, or even a society — lust may be the greatest threat to both civic affairs and one’s personal well-being.

To state it simply, surrendering yourself to lust might compromise the integrity of an entire polis, and your life’s identity itself.

Here then is the Aeneid’s warning on lust, why it’s more corrupting than you think, and how to master your passions against this temptation to fulfill your life’s destiny.

Reminder:

I offer one on one coaching for men, focusing on faith, fitness, and the Great Books. More info here.

Additionally, if you’d like to support my mission of restoring Truth, Beauty, and Goodness to the West, subscribe below!

Called by the Gods

The Aeneid follows protagonist Aeneas, who’s a fugitive of the Trojan War. His hometown, Troy, was sacked by the Greeks, and his family now flee in exile. Thankfully, however, the gods haven’t abandoned him. Venus appears with a message, telling him to take to the seas, as fate has a special plan for him — to found a legendary new empire (Rome).

From this time onward, our hero will be celebrated as “Pious Aeneas.”

In contrast with Homeric heroes who sought personal glory, like Achilles, Aeneas is a unique hero of self-sacrificial duty. His name alone suggests that heroism is being redefined — away from the valor of martial prowess, in favor of piety and concern for one’s neighbor.

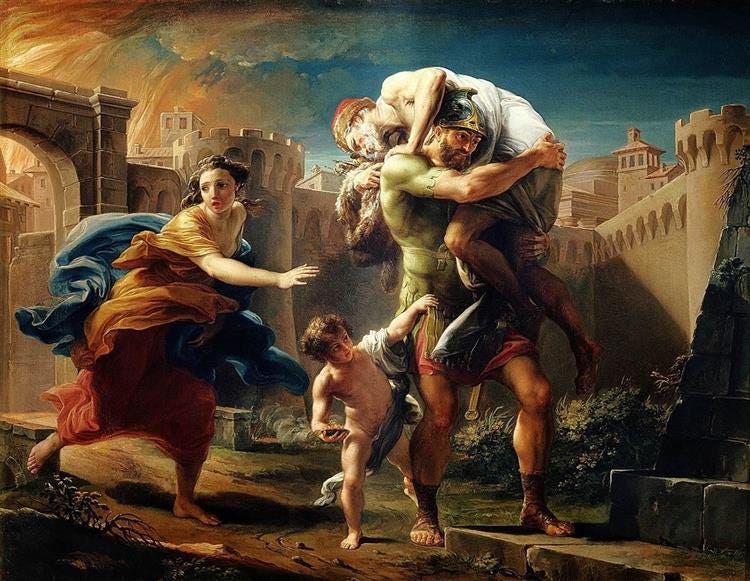

The most striking portrait of Aeneas’ piety appears in his flight from Troy, when he’s carrying his father and son on his back. Figuratively, it showcases he’s fueled by gratitude (carrying his father/tradition), while answering the call to the gods to make a better future for his offspring (carrying his son).

This portrait is the simple key to understanding Aeneas’ character. His destiny lies in self-sacrificial duty:

Can he obey the gods? Will he succeed in founding a new empire?

At first, the answer appears to be yes, unequivocally. Though he’ll have to brave stormy seas, wars, and even the wrath of the goddess Juno, Aeneas has completely surrendered to his fate, and it appears nothing can stop him.

Yet soon Aeneas will face a trial that’s even more difficult than all those mentioned above. It’s a mere temptation that will compromise the integrity of his entire divinely sanctioned mission itself.

The Perfect Match?

As Aeneas takes to the seas, he arrives at the city of Carthage, ruled by Queen Dido.

She takes him in, learns of his tragic backstory, and his divine commission to found a legendary city. In short time, she falls in love with him, and understandably so:

Dido is a virtuous queen herself, and she adores Aeneas’ magnanimity. He’s a great-souled man, destined to be a king, who has laid down his life for his family and faith. His soul is but the reflection of a perfect monarch to compliment her kingdom, and the two begin an affair:

“Whole days with him [Dido] passes in delights,

And wastes in luxury long winter nights,

Forgetful of her fame and royal trust,

Dissolv’d in ease, abandon’d to her lust.”

On the surface, this is a match made in heaven. Two noble rulers, madly in love, whose union could shepherd an entire kingdom into prosperity. Yet this affair is nothing but a grave danger to both Aeneas and Dido.

Aeneas’ danger is simple and straightforward. He’s enamored by temporal pleasures and lusts that have distracted him from his destiny. This affair doesn’t risk his character — that he might become a soft-souled man of sloth — but puts his entire destiny on trial. To stay in Carthage is to deny the call of the gods, and to deny his slain comrades the founding of a legendary empire to continue their legacy.

The moral is clear — submitting your life to carnal pleasure compromises the most sacred aspect of your being, and deprives the world of the virtue and order that you could have gifted it. This simple ethic will become the heart and soul of Roman identity in history.

Aeneas eventually recognizes this danger too. The god Apollo appears to him in Carthage to remind him of his destiny. The hero repents and tragically ends his affair with Dido.

The gods praise him for his piety, but tragically, his decision will have disastrous consequences nonetheless…

Flames and Despair

Dido is heartbroken at Aeneas’ coming departure. She accuses him of treachery, but Aeneas reminds her that it’s always been his destiny to found Rome. To ignore the call of the gods would betray his character, people, and destiny, and drive both of them to ruin. As such, Aeneas sails off to sea, but Dido doesn’t take his departure well.

She goes mad, climbs atop a funeral pyre, and lights it ablaze. For good measure, she slays herself upon a sword too. It’s a grisly death, yet Dido’s example carries a harsh warning with it.

To understand the warning, let’s revisit the lines that begin the affair:

“Whole days with him [Dido] passes in delights,

And wastes in luxury long winter nights,

Forgetful of her fame and royal trust,

Dissolv’d in ease, abandon’d to her lust.”

In the Roman world — which prized duty, civic order, and control of passions — Dido’s affair is a grave mishap. On the surface, the issue is she has surrendered to her passions.

Upon meeting Aeneas, she knew he was fated to leave, but still surrendered mind, body, and soul to her desires for him. But the real issue is deeper than that — she “wastes,” days and nights in her pleasure. Dido’s affair is all consuming such that she’s neglected her duties as Queen.

If “Pious Aeneas,” is a man of self-sacrificial duty, Dido’s affair represents the opposite — two rulers enthralled in selfish-pleasure to the denial of duty.

Dido’s madness then, becomes a mix of both tragedy and moral failing. There’s an element of cruelty in the fickle nature of the gods, along with fates decrees, who call Aeneas away. Yet Dido’s mistake was her self-surrendering to her romantic passions, passions which ultimately consumed her and set her literally ablaze.

Now while this story is indeed tragic, there is a silver lining in the example of Aeneas. It’s not necessarily a “happy,” reprieve, but elucidates a moral lesson of not just mastering your carnal passions, but how to order your soul to achieve your life’s destiny.

Conclusion

This lesson is drawn out if we revisit Dido’s confrontation with Aeneas as he prepares to leave.

Again, when she accuses him of betrayal, Aeneas invokes the Gods — he’s merely submitting to his destiny and has no choice.

Yet Aeneas follows this assertion up with a jarring passage:

“if indulgent Heav’n would leave me free,

And not submit my life to fate’s decree,

My choice would lead me to the Trojan shore,

Those relics to review, their dust adore,

And Priam’s ruin’d palace to restore.”

You’d expect Aeneas to console Dido, to say something like, “if I had free will, I’d marry you in an instant Dido!”

Yet Aeneas doesn’t say this. In fact, he says the opposite. He says if he had free will, he’d go back to Troy and restore the ruins of his fallen city.

Why would Aeneas say this? And why does it matter?

Let’s remember that Aeneas is celebrated for his piety. “Pious Aeneas,” is the man who carries his father and his son — he honors the tradition of his past to build a better future for his offspring… a man of self-sacrificial duty.

The key distinction, however, is that Aeneas wants to restore the city of Troy. His heart’s ultimate joy is honoring his father, city, and the tradition that birthed him. He’s a man of gratitude. This is key when we talk about “self-sacrificial duty”:

Aeneas is not a man who sacrifices pleasure in the name of duty, rather he’s a man who takes pleasure in the self-sacrificing nature of duty itself. It’s this interior desire, this disposition of soul, that makes Pious Aeneas the hallmark of Roman virtue. It’s this magnanimity that inspired the heart and soul of the greatest empire in human history.

In the words of Chesterton:

“Men did not love Rome because she was great; she was great because they had loved her”

So Aeneas and Dido are not to be read as a romance, but a temptation. The King and Queen enjoyed a carnal utopia — a life of lust and pleasure without a want in the world. Their task was to deny temptation in accordance with duty — one to rule a kingdom, the other to found an empire.

Dido’s downfall is a tragedy, but a lesson on temperance.

Aeneas’ story, meanwhile, is filled with heartbreak, pain, and suffering — but it ends in triumph — for he laid his life down for a glory beyond himself. He found gratitude in the past, and was moved by a love of the future, to establish an everlasting virtue in the present. Such duty is the path to building a life, legacy, and even an empire, that truly lasts.

Thank you for reading!

If you’d like to go deeper:

I offer one-on-one coaching for men on faith, fitness, and the Great Books. More info here.

Subscribe for free to receive weekly emails exploring the Great Books and their lessons on Truth, Beauty, and Goodness.

Paid members get an additional members-only email each week!

“Men did not love Rome because she was great; she was great because they had loved her.” Having reverence and respect esteems. It is not shallow, but a deep investment in each other’s welfare. Civic interest shows love. Community circulates love. Fondness finds energetic partners for building with mutual principles. It cannot be bought or pretended. It is the love of the communal good that creates beyond passions and egos.

Thank you for your insights and look forward to reading again after many years.

Is there any (free) translation of this you'd recommend to a guy with a lot of time to read and not a lot of $?