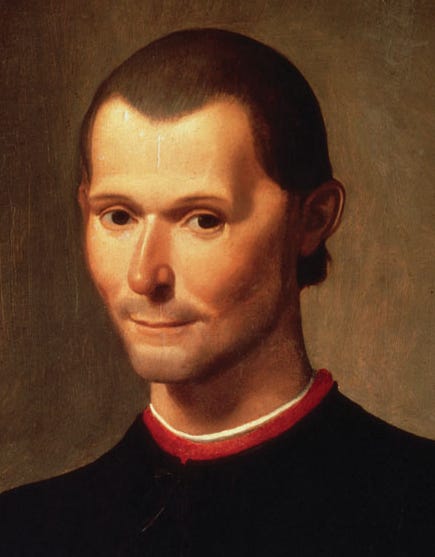

Machiavelli’s Brutal New Morality

Why Power Replaced Virtue in Modern Politics

No work revolutionized modern political thinking like Machiavelli’s The Prince. Though written 500 years ago, it has since established the paradigm of modern politics and influenced some of the greatest philosophical minds today, including Hobbes, Locke, Rousseau, Mill, Kant, Hegel, Marx, Nietzsche, and Dewey to name a few.

But what was it about politics that Machiavelli revolutionized? And what does it really look like in practice?

Today, we’ll analyze this exactly. We won’t just examine the new political theory he introduced, but what it looks like in practice, to get a stark look at the ruthless world of the true Machiavellian politician.

Reminder:

Subscribe, if you’d like to support my mission of restoring Truth, Beauty, and Goodness to the West, subscribe below!

Paid members get an additional members-only email each week!

New Prince, New Morality

In writing The Prince, Machiavelli didn’t merely establish a political treatise, but set out to create an entirely new morality.

Prior to Machiavelli, classical political thinking was intertwined with the Good. As Aristotle posited, man is a political animal who gathers in community to practice virtue. For both pagan antiquity, and Christian medieval civilization, politics were a matter of harmony under virtue oriented toward the logos, or God.

Machiavelli rejects this framework entirely.

His ideal politician is a new sort of ruler, a prince, living in an amoral world:

“A man who wants to make a profession of good in all regards must come to ruin among so many who are not good.

Hence it is necessary to a prince, if he wants to maintain himself, to learn to be able not to be good… according to necessity.”

In effect, Machiavelli says good and evil are irrelevant in politics. The only morality is power, conquest, and acquisition. The new prince’s goal is a rebellion against Plato’s Philosopher King. The latter’s job was to become virtuous, so that he could harmoniously lead his people to the Good, but Machiavelli’s prince solely concerns himself with power, dominance, and personal gain by any means.

Now, let’s see what Machiavellianism looks like in practice, particularly through the lens of one of Italy’s most infamous politicians in world history.

Treachery in Romagna

First, it’s worthwhile to note that many scholars do not consider Machiavelli evil. They say he’s a pragmatist — that he merely teaches us what the world of power looks like, whether we like it or not.

Indeed, whether or not you think Machiavelli evil is beside the point. The man was a genius, and his descriptions of how the world is are remarkably compelling, if not spot on.

However, his brilliance in diagnosing the brutal nature of politics and conquest does not mean that his proposed solutions are inherently justified. An honest look of a Machiavellian world is one that is bleak and hopeless, if not outright evil. To illustrate, look no further than his praise of Cesare Borgia.

He first writes of Borgia:

“I do not know what better teaching I could give to a new prince than the example of his actions.”

He goes on to praise Borgia’s ruthless acquisition of power via murder, force and deceit. The most infamous case is his treachery in Romagna, which Machiavelli deemed, “deserving of notice and of being imitated by others.”

What happened in Romagna?

This was a recently conquered territory that was rebellious to Borgia. He needed to solidify it and ensure his rule over the land. To do so, he installed Remirro de Orco to rule and oppress the people, granting him absolute power.

Remirro was ruthless and tortured the people until they were “reduced to peace and unity.” The Romagnian people came to hate Remirro, yet the nobleman followed Borgia’s orders to a T.

How did Borgia reward him?

Machiavelli writes:

“Because [Borgia] knew that past rigors had generated some hatred for Remirro, to purge the spirits of the people and to gain them entirely for himself… he had [Remirro] placed one morning in the piazza at Cesena in two pieces, with a piece of wood and a bloody knife beside him.”

So Borgia commissioned Remirro to torture the Romagnians, then once they hated Remirro, Borgia publicly sawed him in half so that the Romagnians would love him as a “benevolent,” leader.

Mind you, Machiavelli praises this treachery as the shining example of achievement in Borgia, who is the model Prince that all politicians should seek to emulate.

Wise as a Serpent

So what are we to make of Machiavelli?

The point here is not to moralize, and claim we ought to discard him as a second rate thinker who advocates for evil. He is indeed a genius political thinker with a sharp understanding of how power works, specifically amongst those who reject classical virtue in favor of worldly gain.

We ignore him at our peril.

That said, the new morality he calls for is not one that leads to a prosperous life, rather the opposite.

Man may be a political animal — who needs community to flourish — but Machiavelli makes man an apolitical, anti-social animal. If your chief aim in life is conquest, then your fellow men are subjects to be dominated in a game of power and oppression. Friendship, trust, and love are but mere incidental concepts that can only harm you in your conquest, if you don’t weaponize them first. In other words, to embrace Machiavellianism is to reject all love and comradery with your fellow man.

And that brings me to my next point, that we also ought to discourage the modern temptation of some to “Christianize,” Machiavelli. They attempt to do so by asserting that his goal was to teach good and moral human beings how to become effective in politics, to defend virtue. Yet this was never his intention, and is a clear misreading of both Machiavelli and Christianity, for pure amoral Machiavellianism is incompatible with the Christian doctrine of charity.

Yet Machiavelli still offers much to gain, even for those who reject his amoral pragmatism:

The adage that there is “no purity in politics,” is true, for there are no rules in the political sphere. Moral idealism is an impossibility, and Plato’s Republic of the philosopher king will forever be an unrealized vision. In short, we do need assistance in understanding the convoluted reality of politics and power.

If we’re to take heed in the exhortation to be “wise as a serpent, but harmless as a dove,” no one will teach you serpentine wisdom like Machiavelli. To know the wisdom of modern politics — of amoral power acquisition, and the wayward ways of the Machiavellian man — is to assure one is properly armed in the war of virtue against vice.

The man of justice may be a “fool,” to the Machiavellian, but to embrace the Good in full awareness of evil is the hallmark of wisdom, rather than naivete. In fact, it may just be the wisdom that leads to a true, everlasting virtue — one that endures beyond the rise and fall of all princes, powers, and principalities.

Reminder:

Subscribe, if you’d like to support my mission of restoring Truth, Beauty, and Goodness to the West, subscribe below!

Paid members get an additional members-only email each week!

Machiavelli's outlook sounds very much like the 42 Laws of Power.

I wouldn't be surprised if the latter was inspired by the former.

I love how you framed the issue as a balance between being wise as a serpent AND harmless as a dove, just as Christ told His disciples.

If you err too much on the side of being wise as a serpent, you become an amoral monster. Ironically, if you err too much on the side of being harmless as a dove (radical pacifism), you also become an amoral monster, because you allow your ideals to prevent you from using violence to protect your wife and children from rape, assault, and murder.

In order to be a virtuous person, you need wisdom and harmlessness united.

Like Orwell, Machiavelli's name has become a term unto itself.

The point you bring up about Machiavellianism being misread is crucial. Cherry-picking information is dangerous, especially when dealing with someone whose subject matter is about as consequential as it gets. And I think you're right: the point isn't so much "moralizing Machiavelli," but learning from him. Naivety is by itself a major risk.