Moby Dick and the Unforgivable Sin

Pride, vengeance, and the sin untouched by grace

Why is Moby Dick considered the great American novel?

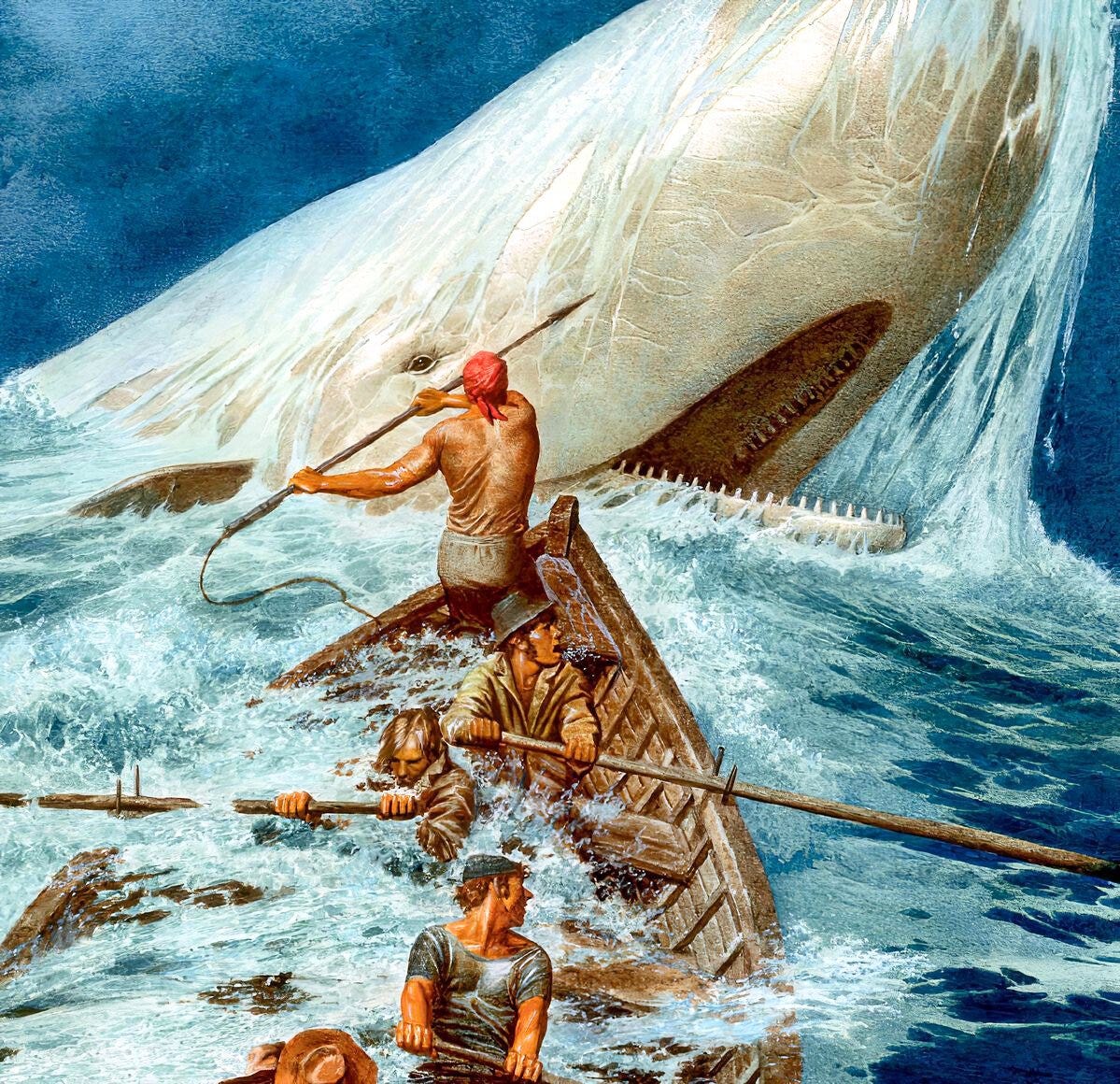

It’s a masterpiece and a warning against vengeance, unbridled ambition, and the unforgivable sin. This book features the infamous hunt of a demonic killer whale, framed with Biblical allusions that prophesize a divine judgment and apocalypse for the whaling crew.

At the heart of this tale is one madman, Captain Ahab, and his monomania which asserts that no amount of bloodshed is too much if it destroys the whale. The story then, is a warning about the grave evil that befell Captain Ahab, and why his evil is far more seductive than you’d think.

Here’s Captain Ahab’s “unforgivable sin,” and what it reveals about human nature, evil, and the pride that corrupts all creation.

Reminder:

I offer one on one coaching for men, focusing on faith, fitness, and the Great Books. More info here.

Additionally, if you’d like to support my mission of restoring Truth, Beauty, and Goodness to the West, subscribe below!

A Prophet’s Warning

The novel begins with protagonist Ishmael, a young man disquieted by idle life in the countryside, whose soul calls him to the seas. He takes a commission aboard a whaling ship, The Pequod, and expects to find a living, and perhaps adventure, by braving the seas. Unfortunately, he’ll soon discover he’s not aboard any regular whaling ship, and his captain is not just any ordinary captain.

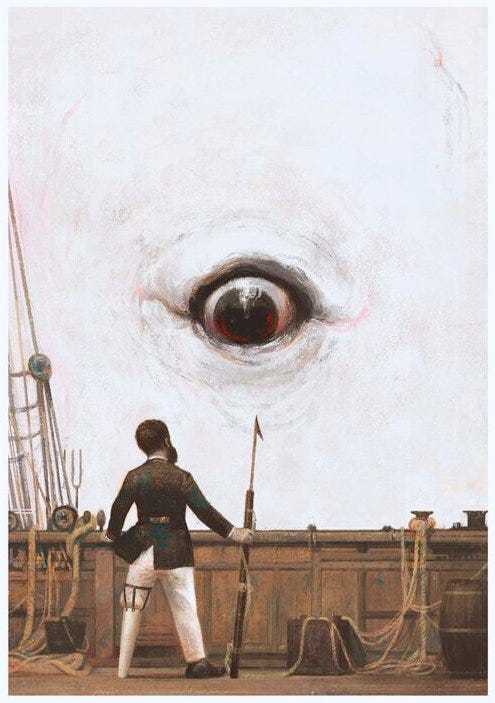

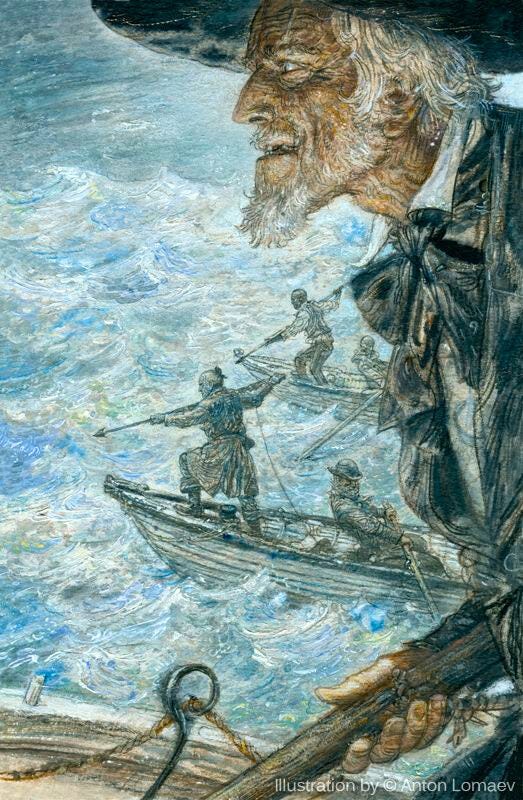

Captain Ahab is the ship’s infamous leader. He’s described as a grizzled older man with the hardened facial features of a long-suffering, vengeful spirit. Most strikingly, he hobbles around on a peg leg, because a great white whale named Moby Dick ate his leg.

Unbeknownst to the crew, and the ship’s owners, Ahab is not planning an ordinary whaling expedition. He has piloted the ship for one purpose — revenge against the whale.

Ahab is ruled by a vengeful monomania to murder Moby Dick. Melville describes his hatred with chilling clarity:

“The White Whale swam before [Ahab’s mind] as the monomaniac incarnation of all those malicious agencies which some deep men feel eating in them, till they are left living on with half a heart and half a lung… All that most maddens and torments; all that cracks the sinews and cakes the brain; all the subtle demonisms of life and thought; all evil, to crazy Ahab, were visibly personified, and made practically assailable in Moby Dick. He piled upon the whale’s white hump the sum of all the general rage and hate felt by his whole race from Adam down”

Ahab views Moby Dick as evil incarnate, as the original sin felt by the human race since the Fall of Man.

As we’ll soon see, things won’t bode well for his crew, and haunting prophecies abode.

Prophecies of Doom

Prophecies warn Ishmael before he even parts to sea.

He first listens to a sermon about Jonah, the unfaithful prophet in the Bible who’s consumed by a whale. Soon after, he gets accosted by a madman named Elijah on the docks, who gives Ishmael a stark warning:

“Ye’ve shipped, have ye? Names down on the papers? Well, what’s signed, is signed; and what’s to be, will be; and then again, perhaps it won’t be, after all.”

In scripture, Elijah was the prophet who urged the wicked King Ahab to repent in vain. The message is clear — Captain Ahab’s quest for vengeance is a selfish mission of pride and wrath that insults against the face of God himself. This Elijah figure warns, “what’s to be, will be,” hinting that Ahab’s mission is fated to doom from the beginning.

What’s shocking, however, is Ahab himself does not seem to care. In fact, he may be full aware that he’s sentencing his crew to damnation. Consider these lines he says of the whale, at various occasions in the novel:

“Towards thee I roll, thou all-destroying but unconquering whale; to the last I grapple with thee; from hell’s heart I stab at thee; for hate’s sake I spit my last breath at thee. Sink all coffins and all hearses to one common pool!”

“I’ll chase him round Good Hope, and round the Horn, and round the Norway Maelstrom, and round perdition’s flames before I give him up.”

“Talk not to me of blasphemy, man; I’d strike the sun if it insulted me.”

Ahab sees himself as a blasphemer who’d strike the sun [God], and will sink “all coffins and hearses,” into a common pool to destroy the whale. Ahab’s crew, his own life, and even Providence itself are all worthy sacrifices if it means he can murder the whale.

It’s what makes Ahab so memorable — he’s a man who donned a Satanic psychology, yet ironically, is using this psychology of evil to purge what he believes to be evil himself. Perhaps it’s no wonder that such a man would gladly destroy himself to destroy the whale…

Yet jarring as Ahab is, we still haven’t gotten to the roots of his own evils, insanity, and quest (semi-spoilers ahead).

Slaying Leviathan

As hinted at in the intro, Ahab is guilty of the “unforgivable sin.”

What exactly is that sin?

St. Thomas Aquinas defines it as a sin against the Holy Spirit:

“if by the sin against the Holy Ghost we understand final impenitence, it is said to be unpardonable, since in no way is it pardoned: because the mortal sin wherein a man perseveres until death will not be forgiven in the life to come, since it was not remitted by repentance in this life.”

The unforgivable sin is a hardened heart that consciously perseveres in grave moral error, unrepentant, onto death itself. It’s easy to see how Ahab fits this picture, but his evil goes even deeper.

How so?

Remember, Ahab believes he’s not fighting a whale, but evil incarnate. His quest is existential — by trying to destroy evil, he’s donning the role of God, and at the same time, questioning God himself:

How can you be just and let evil and suffering reign free?

Let’s remember that, in scripture, Job asks God this same question, and God gives a surprising response:

“Can you pull in Leviathan with a fishhook

or tie down its tongue with a rope?

Can you put a cord through its nose

or pierce its jaw with a hook…?

Can you fill its hide with harpoons

or its head with fishing spears?

If you lay a hand on it,

you will remember the struggle and never do it again!

Any hope of subduing it is false;

the mere sight of it is overpowering.

No one is fierce enough to rouse it.

Who then is able to stand against me?

Who has a claim against me that I must pay?

Everything under heaven belongs to me.”

Leviathan was of course a sea beast. God’s answer to Job about suffering is — the world’s complexities are far beyond human understanding, but everything falls under my Providence:

Mankind’s duty is not to destroy evil, but submit via faith and humility to a God whose justice reigns over all creation.

Ahab, however, rejects God’s answer to Job. He believes he can slay the Leviathan. The man who “would strike the sun,” and blaspheme against God, believes it’s in his power — and perhaps is his very mission — to abolish evil from existence.

Figuratively, Ahab’s life is a shouted curse against God:

Thou art not just, and I’d rather die striking at Leviathan, than submit to thy false decrees.

Such was a hardened heart, welcoming the embraces of death itself, unrepentant, and forever lives on as testimony of the unforgivable sin…

Conclusion

Evil as Ahab may be, readers must admit there’s an attractive nature to his insanity. He’s a fearless man of fortitude, whose cries against fate echo the thumotic grandiosity of Homeric heroes from the Bronze Age.

He’s a sort of anti-hero too, through his reckless ambitions to purge evil from the world on his own accord. Human nature feels a certain admiration for the anti-hero who seeks justice outside the purviews of natural law. Yet it’s these romanticized ambitions — the figurative good intentions that pave the path to perdition — that doomed Ahab and his crew to ruin. If trees are to be judged by their fruits, Ahab’s is none other than death incarnate…

What is the answer to Ahab’s woes?

If the “unforgivable sin” is a heart that refuses to repent, then the cure is repentance — as shown by Job. When God speaks to Job of Leviathan, the suffering man bows in humility. He realizes that despite the world’s evils, he cannot fathom God’s justice, let alone replace Him. The humble will be exalted, but only through faithful suffering.

Hard as this may be to accept, especially when we’re suffering, Ahab’s rebellion reminds us of a grave truth: pride comes before the fall.

You’re free to reject Job, but Ahab’s doom is promised to all who follow his footsteps.

True heroism then, is not slaying Leviathan onto death, but crying out to God from within the belly of the beast, as Jonah did. Such cries, such acts of faith, tend to instill true grace and genuine light in a world otherwise dominated by the dark.

Thank you for reading!

If you’d like to go deeper:

I offer one-on-one coaching for men on faith, fitness, and the Great Books. More info here.

Subscribe for free to receive weekly emails exploring the Great Books and their lessons on Truth, Beauty, and Goodness.

Paid members get an additional members-only email each week!

excellent summary of my favorite book.

it is truly biblical in it’s scope.

at the same time it is uniquely American.

As Twain quipped, “It taught me more about whales than I ever cared to know.”