Schopenhauer and the Metaphysics of Hell

On the True Reality of a Godless World

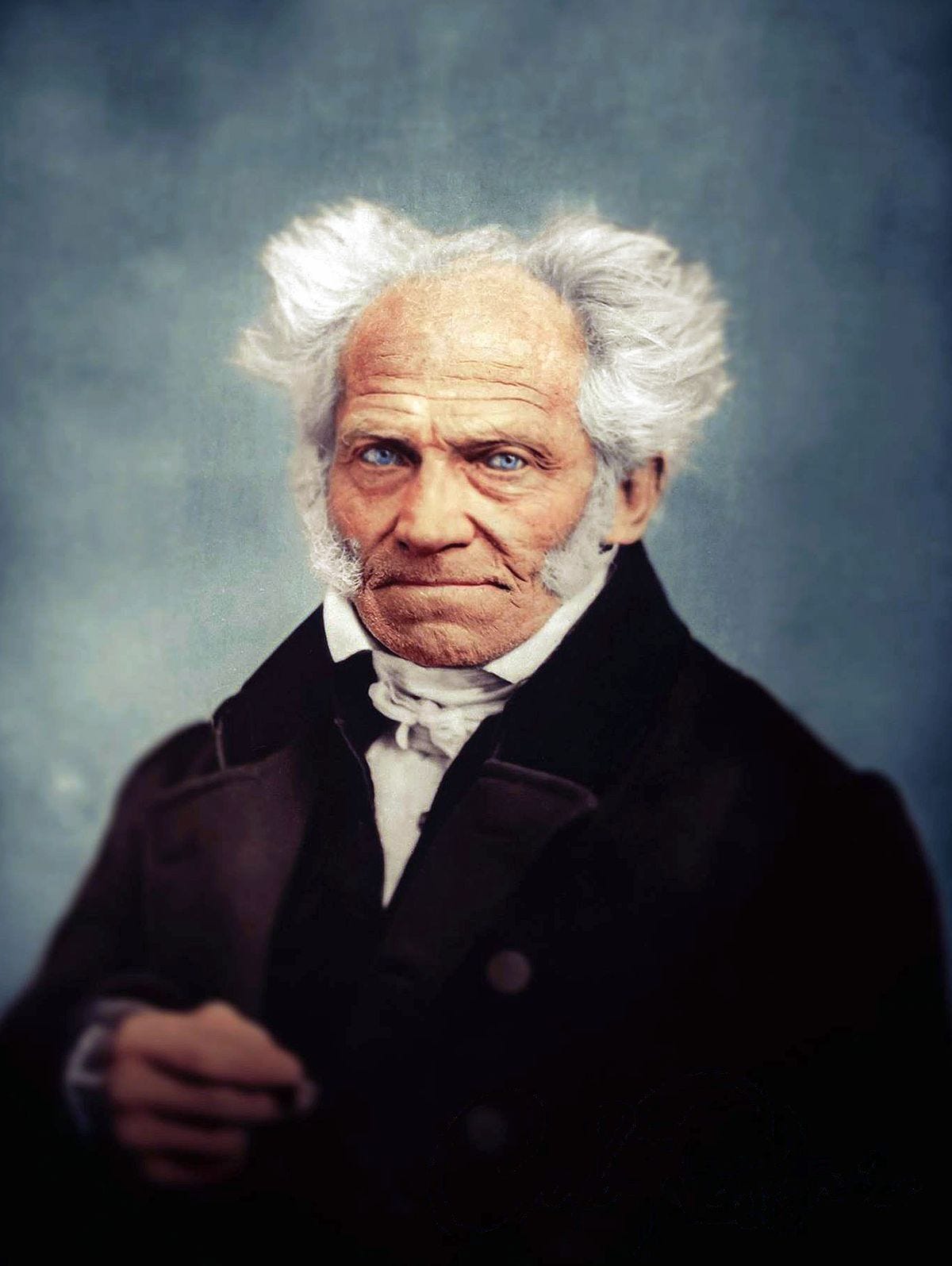

Arthur Schopenhauer is one of the most pessimistic philosophers in human history. He was a bleak man with a bleak life and a bleak belief: that existence itself is suffering.

His worldview was so dark that some scholars have even referred to it as the “metaphysics of Hell.”

Bleak as this vision was, many philosophers claimed it was genius. Nietzsche would later say Schopenhauer was the only true moralist of the nineteenth century. Dostoevsky drew inspiration for his literary villains from this same philosophy. Wagner reshaped his entire artistic identity as a composer to match Schopenhauer’s thought.

So what exactly did Schopenhauer advocate in this metaphysics of Hell? What do we make of a man who claims reality is suffering without redemption—and where, if anywhere, is hope to be found in such darkness?

Today, we’ll descend into the abyss of pessimism to see whether any true lights can endure through Schopenhauer’s wrath.

Reminder:

Subscribe, if you’d like to support my mission of restoring Truth, Beauty, and Goodness to the West, subscribe below!

Paid members get an additional members-only email each week!

Early Life

It’s not difficult to see why Schopenhauer developed such a bleak philosophy. His early life was tragic, lonely, and antisocial. It would be unfair to say tragedy alone caused his philosophy, but it’s worthwhile to consider that he suffered deeply, especially in his familial life.

His father committed suicide when Schopenhauer was young. His mother, by most accounts, was cold and austere. The two were frequently at odds, and eventually she expelled him from the home. In one letter, she wrote:

“You are unbearable and burdensome, and very hard to live with; all your good qualities are overshadowed by your conceit, and made useless to the world simply because you cannot restrain your propensity to pick holes in other people.”

Despite this tragic separation, Schopenhauer was financially secure. He lived off his father’s inheritance, which he invested wisely, freeing him from the need for academic patronage or public approval. As a financially secure young man, he devotedly himself to rigorous academic study.

At first, Schopenhauer immersed himself in Plato, Kant, Fichte, and the central figures of the Western philosophical tradition. Yet his most distinctive insight came from an unexpected source: Eastern philosophy.

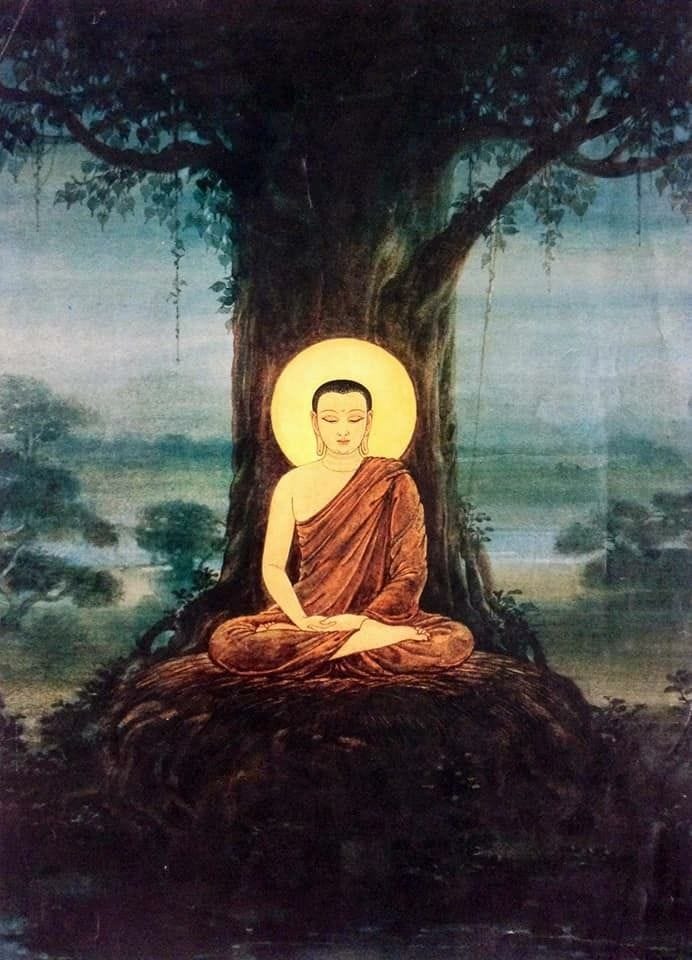

Schopenhauer held Buddhism in high regard and revered the Upanishads, writing:

“In the whole world there is no study so beneficial and so elevating as that of the Upanishads. It has been the solace of my life; it will be the solace of my death.”

What did he find in these texts? What did Eastern philosophy, filtered through Kantian metaphysics, offer him?

And most important — why did these ideas which brought him solace ultimately give rise to one of the most pessimistic systems ever constructed?

It all traces back to a single idea that fueled Schopenhauer’s philosophical grandeur.

A World of Illusion

There’s no way I can speak about buddhism and hinduism with fair depth in this short post, but if there was one core idea they impressed upon Schopenhauer, as he understood it, it’s this:

The world is an illusion of suffering that one must escape from.

Eastern orientalism is perhaps united by a skepticism of the world, believing reality to be a dream to wake up from, or a world to escape. Buddhism calls it nirvana, Hinduism Brahma, but both agree that life becomes an awakening into a divine reality in which all is one.

A classic western critique, however, is that this stance destroys all meaning of lived experience in the material world. If all is a dream, then nothing objectively matters in the here and now.

For someone like Schopenhauer, however, this eastern cosmology became a profound sense of joy. It gave a name to his despair, and helped him formulate his own philosophy, which he synthesized with Kant and the Western tradition.

He wrote it down in his masterpiece — The World as Will and Idea — which explains why life is suffering, why the human condition is doomed to despair, and the only two paths humanity can follow to escape their horrible lot.

The World as Will and Idea

The World as Will and Idea is a philosophy that can be summarized in 3 main ideas:

1. The World is a prison

Schopenhauer argues that the world as we experience it is like a prison. He compares human consciousness to Shakespeare’s Hamlet: the ego trapped in despair and uncertainty, alienated from reality itself.

Though the material world exists, we never encounter it directly. We experience only representations — images shaped by our senses and minds. We are confined within a subjective world we can never fully escape.

2. The Will Can Be Known

We cannot know the world, but we do have direct access to our will, or “the self.” But this access is pessimistic — Schopenhauer says we may have true access to ourselves, but we can never really know ourselves in the classical sense of the word.

We can never, through rational self-knowledge, grow virtuous by nature and master our character. Our self-knowledge, for Schopenhauer, is just a realization that we are a will of desires that we can never be satisfied with permanence.

He calls the will a blind, a teleological force that animates all reality, and ultimately controls us. In a sense, we’re controlled by something authoritative and all pervasive (like God), only its bestial and less than God. You might say man is made in the image of the beast.

Our desires control us, but are never satisfied. Hence, life is what the buddhists say — an illusion of suffering, a dream to be escaped from — only Schopenhauer laments it a prison.

Both share a longing for death, and abolition of self

3. Escaping the Prison

Schopenhauer says there’s two ways to escape this prison, or at least make this brutal life liveable.

Aesthetics. Art is relief from suffering. To make good, creative art is to capture true representations of life. To dramatize the world beautifully is to transcend the world. You blissfully dissolve yourself into immersion with reality.

Ethics. Schopenhauer says the Christian saints and Buddhist monks both reach nirvana through universal compassion. They know and share in the suffering of others, and their compassion overwhelms the boundaries of the ego.

In other words, only sainthood or artistry help you escape the prison of self, and suffering.

At this point, Schopenhauer still gives us reason for despair. Life, for him, is suffering without redemption. It may be numbed via art or compassion, but never truly healed.

And yet, even this grim philosophy has a final telos.

Schopenhauer offers one true path of escape, drawn from a wisdom shared by both Eastern mystics and Western ascetics… but this escape is not comforting, not affirming, and not meant for everyone.

If Schopenhauer is right about the nature of the world, then his proposed solution is the only possible answer to an existence defined by suffering without redemption.