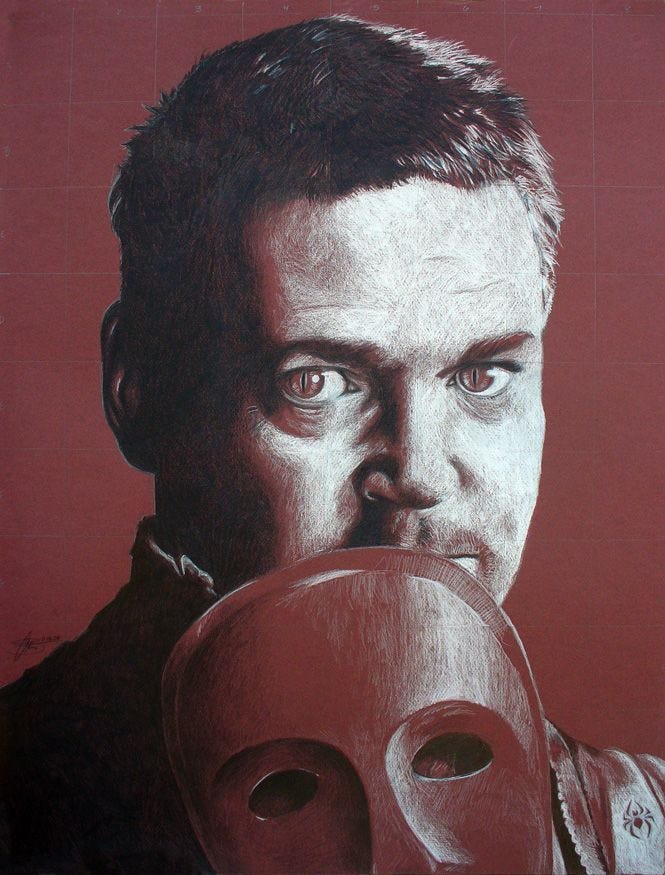

Shakespeare's Most Terrifying Villain

Analyzing the Psychology of Pure Evil

Shakespeare’s works feature countless murderers, liars, adulterers, and schemers, but none are as depraved as Iago.

The primary antagonist of Othello, Iago has baffled literary critics for 500 years. His evils are so twisted, they defy explanation. Few literary characters have drawn more critical commentary than Iago, and yet no one can agree on his true motives or desires.

In short, he’s feared by all, but understood by none.

It’s precisely this mystery that makes him so chilling, and reveals why the truest expression of evil always defies comprehension.

Today we’ll look at several traits that make Iago unique depraved, not just within Shakespeare’s canon, but in all of literature, and discern what he teaches us about combatting pure evil.

Reminder:

Join me on Dec 10 for a live discussion where we’ll explore how to recover the education modernity stole from us.

Seats are limited — reserve your spot now and start rebuilding your intellectual foundation:

A Villain of Twists and Turns

First, let’s ground ourselves in the story.

Othello follows its protagonist, Othello, who is a Moor in 16th-century Venice. He’s just married the noble woman Desdemona, and also earned himself a military promotion. Othello is sent to Cyprus on an expedition, accompanied by his wife and a small military envoy.

Among this group is Iago, who now serves under Othello.

He introduces himself to the audience with a chilling soliloquy, openly declaring his desire to destroy the Moor:

I hate the Moor:

And it is thought abroad, that ’twixt my sheets

He has done my office: I know not if’t be true;

But I, for mere suspicion in that kind,

Will do as if for surety…

The Moor is of a free and open nature,

That thinks men honest that but seem to be so;

And will as tenderly be led by the nose

As asses are.

I have’t. It is engender’d. Hell and night

Must bring this monstrous birth to the world’s light.

Right away, his speech curses the narrative with tension. Iago claims to hate Othello for allegedly sleeping with his wife, yet in the same breath describes Othello as “free and open,” a man honest by nature. It’s as if he contradicts himself without hesitation, and casts Othello’s alleged crime into doubt.

Even more confusing:

Earlier in the act, he told Roderigo he hated Othello because of the promotion. This pattern will continue, Iago’s motives for his hatred will continue to contradict each other. His only consistency is inconsistency, and a desire to destroy all who come in his path…

From this moment on, the rest of the play functions like a puppet show in which Iago pulls every string, manipulating and ruining everyone in his path.

And this brings us to the next striking aspect of Iago’s villainy.

Amongst Bad Company

In Dante’s Inferno, the lowest levels of hell are reserved for liars, frauds, and deceivers. Judas, Brutus, and Cassius — betrayers of the highest order — are cast into the jaws of Satan himself.

By Dante’s logic, Iago fits perfectly among them. He is nothing but a man of lies and deceit. As he famously declares:

“I am not what I am.”

This line is arguably the reason critics have been baffled by Iago for centuries. Again, his only consistency is inconsistency. He loves deception for its own sake. Anyone who interacts with him gets drawn into his web and has their perception of reality distorted.

Classically, lying is considered the gravest of evils, worse even than physical violence, because it corrupts the intellect in man, which reflects the divine. The greater the corruption, the greater the evil. Iago’s evil is not merely that he brings harm upon others, but corrupts them to reflect the very evil of his own soul.

As examples, one can look at the degradation of Cassio, Roderigo, and most notably Othello, a once great-souled war hero who becomes a jealous, impotent, husk of his former self by the play’s end.

It’s this pattern of corruption that feeds perfectly into the next unique layer of Iago’s evil.

Beyond Good and Evil

Iago’s lies aren’t even the most chilling part of his character. More terrifying is his outright denial of good and evil altogether.

At first, this might not sound extreme — moral relativism is common today anyways — yet most relativists still cling to vague notions of “progress,” or “humanity.” They’ll still say slavery or murder is “wrong,” even if they can’t explain why.

Iago is one of the rare characters who truly denies morality at its root, and embodies Dostoevsky’s warning that “without God, anything is permitted.”

Consider this line from Iago:

“What’s he then, that says I play the villain?”

It’s almost stunning that the man plotting the murder and downfall of many himself denies villainy. Yet this statement is perfectly logic for Iago. He doesn’t deny villainy because he believes he’s secretly good, rather he rejects the categories of good and evil altogether. He is waging war on the moral law itself, and his philosophy effectively amounts to:

I’m not evil, but I’m embracing evil to prove to you that evil doesn’t exist.

It’s contradictory, even self-destructive, but for a man like Iago it’s perfectly logical.

This brings us to the climax, and the most terrifying aspect of his character.

A Dreadful Silence

The tragedy of Othello resonates because its hero begins the play as one of Shakespeare’s noblest figures. The protagonist Othello is a good man driven to commit terrible evil because a great villain corrupted his virtues into vices.

Yet Iago’s final, and most striking blow, doesn’t come through the success of his conspiracy and its bloodshed.

His most terrifying moment, perhaps his triumph, comes when Iago is apprehended.

The authorities demand Iago give an explanation for his crimes that have led to countless deaths. After so many soliloquies, in which Iago has dominated ⅓ of the play’s entire dialogue with his speeches, the reader is finally anticipating a true answer to make sense of Iago’s depravity… but Iago gives the worst answer possible:

Nothing.

He vows silence to the grave and is dragged offstage without ever revealing his true motive.

This is the final horror. Though captured, Iago achieves the very result his creed implies. The man who spent the play destroying others’ perceptions of truth ends by destroying even the truth about himself. It is the ultimate enactment of his philosophy he stated earlier:

“I am not what I am.”

It is an inversion of the divine name proclaimed in Scripture:

“I AM WHO AM.”

God is Truth, Being, Goodness, but Iago is the opposite — evil, corruption, and non-being.

He destroys all he touches, including himself, and revels in that destruction.

Indeed, it’s in this very void of bloodshed and silence that Shakespeare’s greatest villain triumphs.

Conclusion

How do we grapple with pure evil as embodied by Iago?

Iago is not someone you can “defeat.” A man who revels in self-destruction will always destroy himself, and many others along the way.

But we can deny him victory. Iago never sought to kill Othello; he sought to corrupt him. Evil triumphs not by force, but by deprivation and corruption of the Good..

Thus the true answer to Iago’s depravity is simple, but difficult:

Do not become Iago. Or, in other words, do not be corrupted as his victims were.

Evil is a parasite — it feeds off the good, and therefore, triumphs when goodness corrupts itself. But those who maintain virtue, even amongst fraud and deceit, testify to a providence in the cosmos that runs far beyond the schemes of the wicked.

Hold evil to account, but do not be too quick to deal out vengeance. On that note, Tolkien says:

“Many that live deserve death. And some that die deserve life.

Can you give it to them?

Then do not be too eager to deal out death in judgement.

For even the very wise cannot see all ends.”

Indeed, be led by virtue in all things, for in totality, virtue stands over the decay of the wicked.

Reminder:

Don’t miss this opportunity to participate in a live discussion on Dec 10 about reclaiming the education modernity abandoned. Seats are limited — claim your spot here:

Thanks for the post. It's good to be reminded that people are still thinking about these questions and are actually reading Shakespeare. What struck me most in this essay was how strongly it echoes Coleridge’s insight into Iago, especially his remark about the “motive-hunting of motiveless malignity.” Reading your analysis took me back to my first encounters with Coleridge’s lectures on Shakespeare, where he tried to make sense of the same unsettling quality you describe so well: Iago’s evil isn’t grounded in any real motive. It seems to create itself out of contradiction.

There was something unexpectedly nostalgic about that. Coleridge understood that Iago disturbs us because he cannot be reduced to psychology or circumstance. He becomes a kind of pure force of corruption.

I don't have too much to add other than I loved reading this. Great topic, very well written. Iago has always been a favorite of mine.