The Greatest Myth of the Modern World

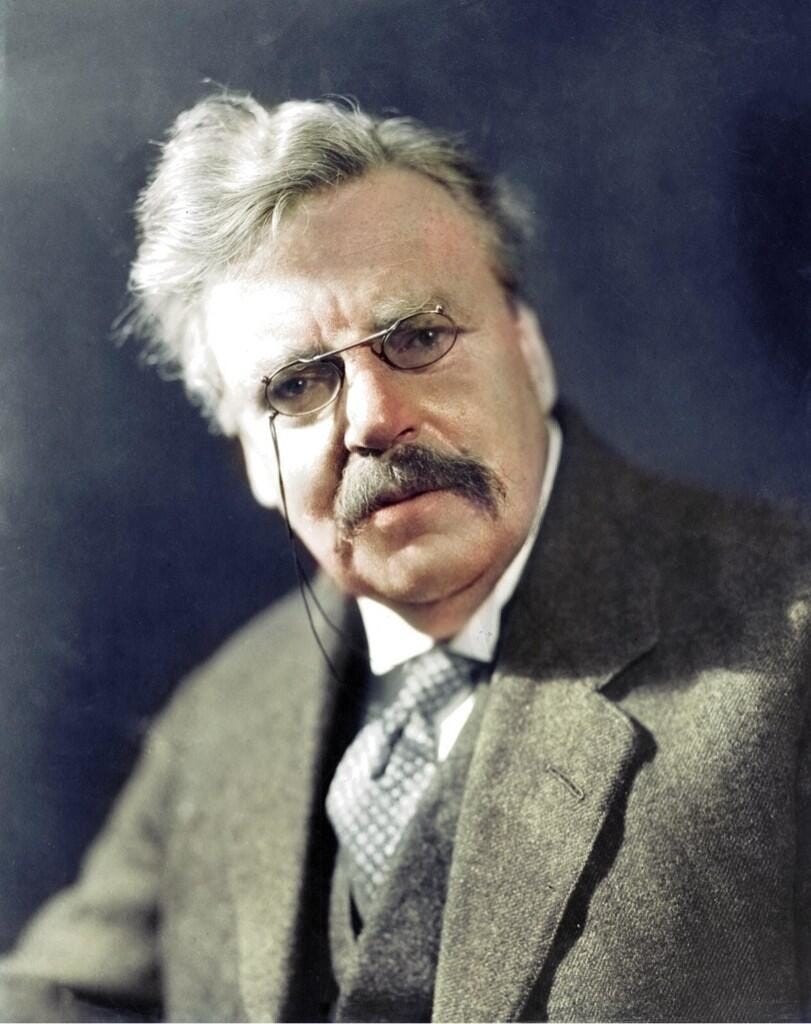

Chesterton's Takedown of Modern Atheism

G.K. Chesterton’s The Everlasting Man is one of the most underrated books of the twentieth century. It is a work of Christian apologetics, celebrated as a masterpiece precisely because it does very little in the realm of formal apologetics.

Chesterton’s argument for Christianity is not powerful because of its positive proofs, but because of what it exposes about modernity. Put simply, Chesterton helps you understand the “founding myth” of modern man. Once you see it, you begin to realize that many of the so-called “self-evident truths” of contemporary society are in fact lies.

How powerful is this argument?

For what it’s worth, former atheist C.S. Lewis credited The Everlasting Man more than any other book with helping inspire his conversion to Christianity.

Today then, we’ll explore the key ideas of The Everlasting Man: including what they reveal about the “founding myth” of modernity, and how they help us rediscover long-forgotten truths in modern society.

Reminder:

Subscribe, if you’d like to support my mission of restoring Truth, Beauty, and Goodness to the West, subscribe below!

Paid members get an additional members-only email each week!

What is a Founding Myth?

First, let’s explain what a “founding myth,” is.

Put simply, a founding myth is the metanarrative a civilization tells itself in order to establish its identity. The Roman Empire, for example, embraced Virgil’s Aeneid as its founding myth. It tells the mythic story of pious Aeneas, who obeys the decrees of the gods and lays the foundations for what would become Rome. In doing so, it taught Romans to see themselves as a people defined by duty, piety, and civic responsibility. It gave them a shared narrative and moral vision—an answer to what it meant to be Roman.

The same can be said of Homer for the Greeks, and of Christianity for later civilizations. Tolkien famously called Christianity the “true myth,” because it possesses all the structures of a great myth while being rooted in real history.

So we may grant that civilizations of the past embraced founding myths. But the question remains:

Does modernity have one?

At first glance, it sounds strange to accuse modernity—an agnostic, secular civilization—of embracing mythology. After all, few, if any, great myths emerged in the Western literary tradition after Christ.

Yet while modernity may lack formal myths, modern man still tells himself a story about his origins. Chesterton lays out that story succinctly in The Everlasting Man. I’ll paraphrase it here, and you can judge whether this “story” sounds familiar.

The founding myth of modernity suggests this:

Mankind is a product of evolution, descended from apes, gradually awakening into pure rationality. Once we were cavemen—mistaking lightning for God and scratching primitive images onto stone. Over time, we shed this ignorance, gained mastery over nature, and outgrew superstition. Religion, on this view, was merely a transitional phase in humanity’s ascent.

In the end, mankind is expected to become fully rational, using reason alone to master nature completely—ushering in a utopian future free from suffering, superstition, and constraint.

This story lacks the grandeur of ancient myths, but it is a founding myth nonetheless. Let’s explain why.

Modernity’s Myth

One might accuse Chesterton of being anti-science, expecting him to launch an attack on evolution itself, but this is not his argument. Chesterton is largely indifferent to whether evolution is true or false.

His concern is not evolution as a scientific theory, but the unscientific philosophical conclusions that are smuggled in and asserted with absolute certainty. Notice that the “founding myth” described above is not a scientific account at all. Rather, it uses the authority of science — specifically evolution — to construct a narrative about mankind.

This “myth” has all the features of a philosophical metanarrative, including:

A cosmogony: matter → life → mind

A fall upward: ignorance → enlightenment

A salvation arc: science → mastery → utopia

An eschaton: fully rational, liberated humanity

At this point, a natural objection arises:

Perhaps myth belongs to humanity’s childhood, and modernity represents our coming of age. But this objection already assumes what it must prove. Human beings do not merely discover facts about themselves; they inevitably interpret them. We cannot encounter our origins, our purpose, or our destiny without arranging them into a meaningful whole. In other words, man cannot help but tell a story about himself.

The answer to this objection, however, is that:

A civilization may reject old myths, but it will never live without some account of where it came from, what it is becoming, and why any of it matters. To abandon myth is not to become purely rational; it is simply to adopt a new myth while denying that it is one.

Chesterton’s argument, then, is straightforward. The story we tell ourselves about cavemen and prehistory is not a narrative derived from science. It is a philosophical argument, asserted without evidence, while hiding behind scientific authority. Chesterton is not primarily concerned with whether this narrative is true or false; he wants us to recognize it for what it is—a myth.

He summarizes the point well:

“Nobody can imagine how nothing could turn into something. Nobody can get an inch nearer to it by explaining how something could turn into something else. It is really far more logical to start by saying ‘In the beginning God created heaven and earth’ even if you only mean ‘In the beginning some unthinkable power began some unthinkable process.’ For God is by its nature a name of mystery, and nobody ever supposed that man could imagine how a world was created any more than he could create one.

But evolution really is mistaken for explanation. It has the fatal quality of leaving on many minds the impression that they do understand it—and everything else.”

The Wisdom of a Child

So what are we to conclude?

What is Chesterton’s purpose in exposing the founding myth of modernity?

Once again, Chesterton is not attacking science, but bad philosophy hiding behind scientific authority. His aim is to defend the good name of science — drawing sound conclusions about nature from observable phenomena — while also rescuing philosophy and theology from corrosive skepticism.

The answer, then, to reviving our decaying intellectual tradition is a return to the wonder of a child:

“But when fundamentals are doubted, as at present, we must try to recover the candour and wonder of the child; the unspoilt realism and objectivity of innocence. Or if we cannot do that, we must try at least to shake off the cloud of mere custom and see the thing as new, if only by seeing it as unnatural.”

This childlike wonder echoes the Socratic claim that wonder is the beginning of wisdom. The central problem of modernity — an age of agnostic skepticism — is that it has lost its sense of wonder. What united the high pagans of antiquity and the Christians of medieval Europe was precisely this posture: the former sought the logos, the latter sought God.

Both knew that they knew nothing, yet both pursued Truth, Beauty, and Goodness with the conviction that these things could be known.

The cure for small-minded sophistry is great-spirited wonder. It requires a leap of faith — if not in God, then at least in the existence of a transcendent, intelligible truth. To believe that Truth exists, and to seek it, is to begin the process by which all old things are made new.

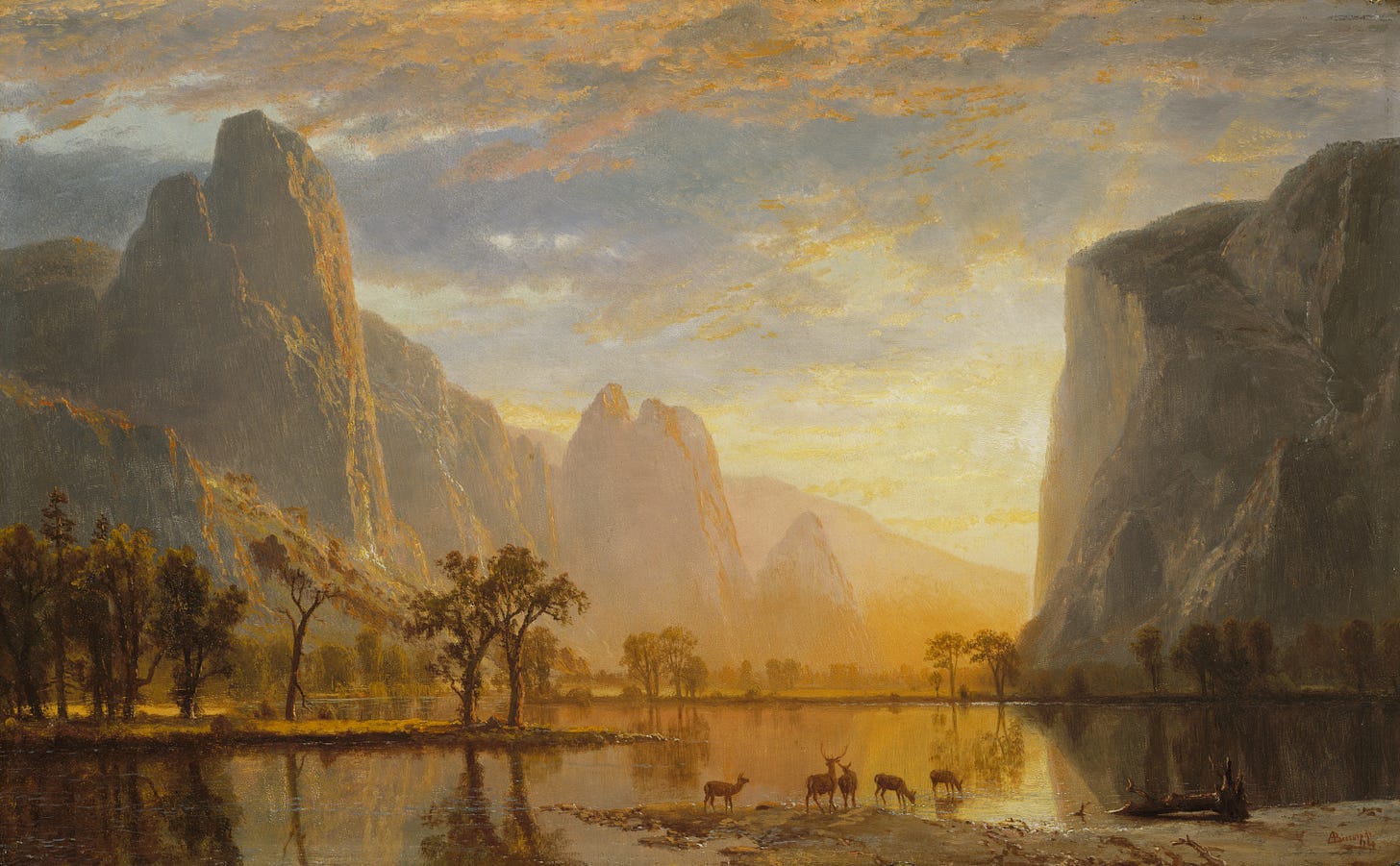

It is to rediscover the wonder of a once-lost world. To see reality again through the eyes of a child—even in adulthood… It is, in a real sense, to be born anew.

Reminder:

Subscribe, if you’d like to support my mission of restoring Truth, Beauty, and Goodness to the West, subscribe below!

Paid members get an additional members-only email each week!

Well written! Faith is the fundamental difference between religious myth and modernity’s myth. Properly understood, faith is not blind assent or intellectual laziness. It is an acknowledgment of limits, of mystery, contingency, and dependence on a reality that exceeds human mastery. Faith begins with the admission that I do not fully know, and therefore it cultivates humility.

Modernity’s myth, by contrast, tends toward absolute conviction precisely because it refuses to see itself as a myth at all. Its story of progress, rational mastery, and inevitable enlightenment is treated not as an interpretation of reality, but as reality itself. Because this narrative claims the authority of science, it often immunises itself against philosophical or moral questioning. Doubt is permitted only within tightly controlled parameters, while doubt about the framework itself is treated as irrational or dangerous.

This is why modern ideological certainty so often produces fanaticism rather than openness. When a worldview is believed to be not merely true, but self-evident and final, disagreement is no longer an invitation to inquiry. It becomes a moral failure. Ironically, this posture is far closer to dogmatism than to reason.

Faith restrains the intellect by reminding it that truth is something to be sought, not possessed absolutely. Modernity’s myth, lacking that restraint, mistakes confidence for clarity and conviction for understanding.

I've had a realization recently. That we are very insignificant as compared to the rest of the universe. And no matter how much we think we know, there are still so much more that we do not know.

Suddenly, I felt a shift in my perspective. And while I was unsure before, now I don't think I could call myself an atheist, or totally dismiss the existence of a God. Given the vast universe, I realized that while it is difficult to claim that God exists, it is much more difficult to prove that God does not exist.

It doesn't mean I'm anti-science all of a sudden. But perhaps science has kind of skewed our perspective starting in the modern era. We think of science as the electric bulb that fills the room with light so you can see everything. So everything becomes small, and can be reduced into mathematical equations.

Rather, I'd like to think that science should feel like carrying a candlelight in a dark room. That it illuminates only to reveal that the room is so much bigger, and we have yet to see eveything. And it could feel scary, but then it starts to spark our imagination. Precisely because, we have limits to what we know.

This way of thinking changed a lot for me. Suddenly, I feel like a child again, curious about the endless possibilities. Perhaps, there are such things as fate or destiny. Perhaps there are more to things that we see. There is beauty all around, and perhaps there's a message behind them like constellations in the skies. The shift in perspective changed a great deal for me, without having to discard science but also having an openness to myth. I both know so much and so little at the same time.