The Literary Club That Changed the World

And the Source of Tolkien and CS Lewis' Genius

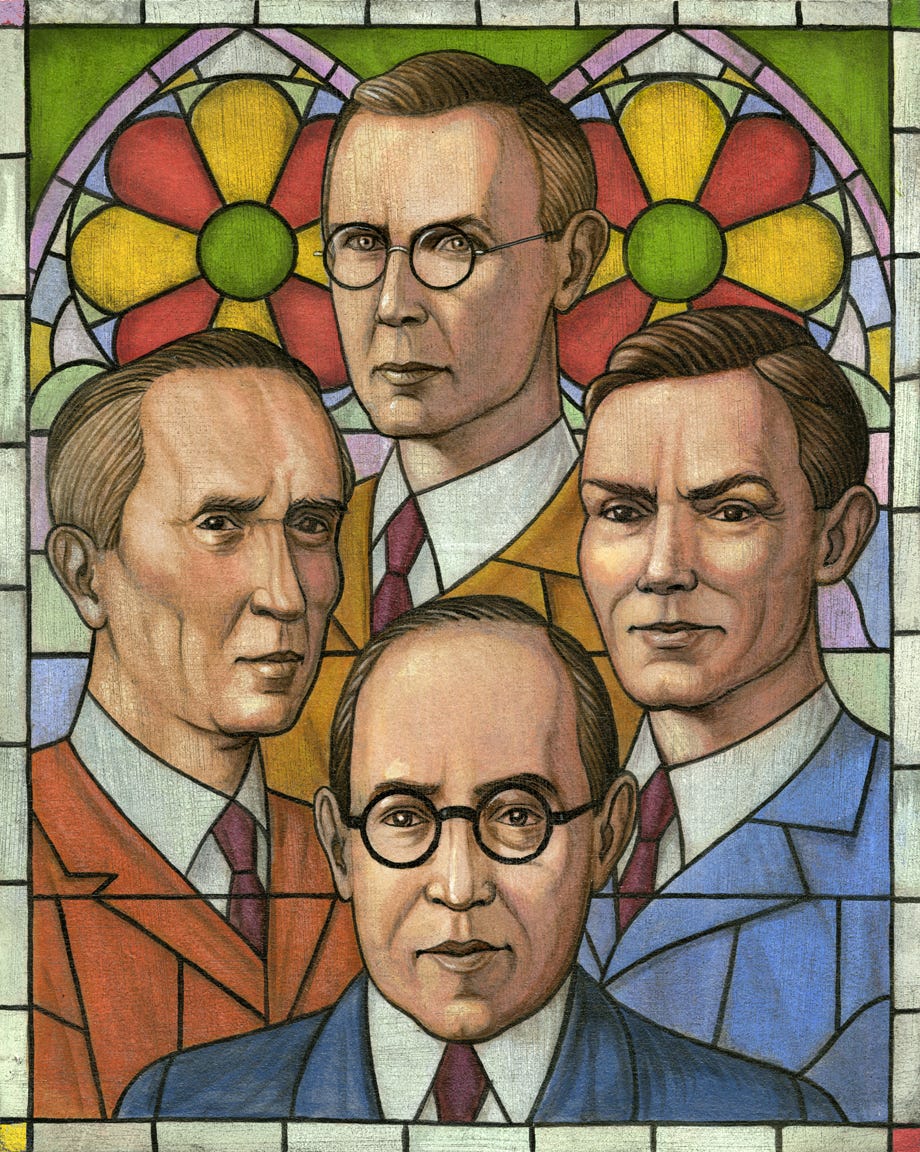

Tolkien and C.S. Lewis were among the most influential thinkers of the 20th century.

The Lord of the Rings and The Chronicles of Narnia are among the best-selling novels in human history, yet that’s only the surface of their work and legacy. Lewis was the century’s most influential Christian apologist and chief lay theologian of England. Tolkien’s scholarship in academia reshaped our understanding of language, culture, and anthropology.

One wonders how these two men became such geniuses.

On the surface, they seem supernatural and larger than life (perhaps graced by God, haha), but a closer look shows their genius was no accident.

Among their many influences, one stands out with particular force — The Inklings.

This literary group preceded, sharpened, and helped birth both of their geniuses, and transformed the intellectual and literary landscape of the West during the darkest hours of the 20th century.

Today, we’ll look into the Inklings, including their legacy, their discussions, and how virtuous friendship forges human genius.

Reminder:

Join me TONIGHT for a live discussion where we’ll explore how to recover the education modernity stole from us.

Seats are limited — reserve your spot now and start rebuilding your intellectual foundation:

The Members

The origins of the Inklings begin with Lewis and Tolkien’s personal friendship.

Both were Oxford scholars who loved antiquity and lamented the state of the modern world in the mid-20th century. Political ideology ran rampant, WWII loomed, and pessimism was at an all-time high. Literature reflected this decline, and both scholars felt modern fiction and non-fiction were horrid.

Lewis, speaking with Tolkien, once said:

“If they won’t write the kind of books we like to read, we shall have to write them ourselves.”

Thus, the Inklings were born.

Tolkien and Lewis were the most famous, but many other brilliant minds joined them:

Owen Barfield — philosopher, poet, literary critic. He believed myths were pneumatic dramatizations of primordial man — carriers of ancient knowledge forgotten by modernity. His ideas influenced both LOTR and Narnia.

Hugo Dyson — Oxford literature scholar with an expertise in classicism. He was the group’s harshest literary critic, yet his criticism forced the Inklings to refine their writing. He famously disliked LOTR, but his classicism ensured literary rigor.

Charles Williams — poet, novelist, theologian. Williams added mystical and moral depth to the group. His novels blended suspense with spiritual insight and influenced both Tolkien and Lewis. He likely inspired Tolkien’s theory of “sub-creation.”

Importantly, the group wasn’t limited to writers. Members like Robert Havard (a doctor) and Adam Fox (Dean of Divinity at Magdalen) show how diverse the fellowship truly was.

In all, around twenty members participated — men of varied backgrounds, professions, and worldviews.

Yet amid this diversity, one point of unity held the group together. And that unity forged the genius of every member.

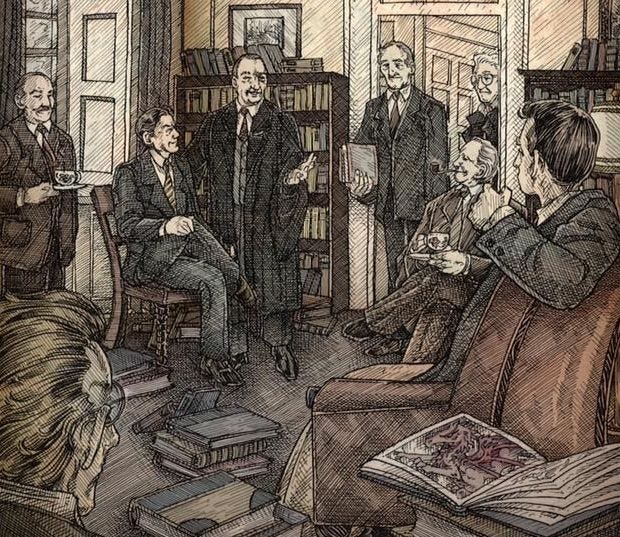

How It Worked

So how did the Inklings actually function?

The concept was simple: they met at a local pub — The Eagle and Child — to debate ideas, discuss philosophy and theology, and critique each other’s writing.

On the surface, it looked like any other literary club.

What distinguished them was a subtle but essential principle, summed up by Warren Lewis:

“We were no mutual admiration society: praise for good work was unstinted, but censure for bad work—or even not-so-good work—was often brutally frank.”

This may surprise those used to the gentle public personas of Tolkien and Lewis. But privately, every Inkling took his craft with utmost seriousness.

The group was united by a fervent love of truth — in philosophy, theology, and literature. All were welcome, but you had to show up ready to debate, engage, and defend your ideas.

In short, the Inklings were a living example of “iron sharpens iron.” Their friendship forged their genius, but it was a friendship of proverbial fire — heated debates, disagreements, even fights.

Hugo Dyson openly lambasted LOTR. Tolkien and Lewis clashed many times. But that is precisely the point: virtuous friendship sharpens the soul, and purification often comes through good-faith disagreement grounded in truth.

Tolkien dedicated the first edition of LOTR to the Inklings, and Lewis said of them:

“What I owe to [the Inklings] is incalculable.”

The virtuous friendship of a few did not just shape their careers, rather it literally changed the world.

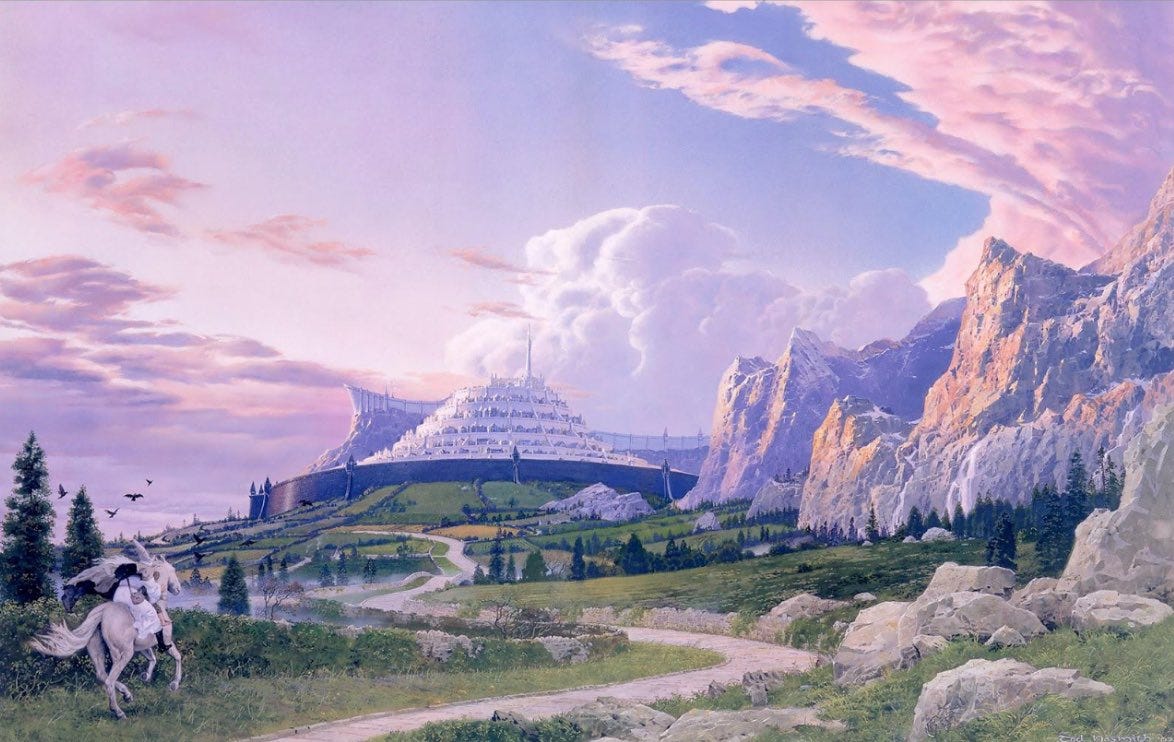

To Narnia and Beyond…

The surface-level impact of the Inklings is easy to see:

LOTR and Narnia have each sold hundreds of millions of copies and spawned global multimedia empires that remain influential nearly a century later.

Yet even that does not fully capture what Tolkien, Lewis, and the Inklings achieved. They reshaped the modern imagination itself.

Their work emerged in a century dominated by the “Lost Generation,” marked by despair and a rejection of truth, beauty, goodness, and God. Nihilism and pessimism were fashionable, while hope and faith were antiquated ideals of naivete.

The Inklings helped modern man rediscover not mere optimism, but a genuine longing for the transcendent and eternal. It is perhaps too simplistic to say they restored faith in God, but they certainly helped rekindle something prescient, good, and true in the human heart. As Samwise says:

“There is still some good in this world, Mr. Frodo, and it’s worth fighting for.”

This was precisely why Tolkien and Lewis flourished. Their circle did not write bland academic arguments nor simplistic spiritual fables, rather they demonstrated that myth, fantasy, and allegory are the tools that reconnect modern man with his soul. Myth teaches us justice, goodness, courage, the reality of evil, and our dignity as image-bearers of the divine.

So yes, in the end, the Inklings helped modern man remember who he really is… while the rest is history.

Conclusion

Ultimately, the Inklings point us back to the true purpose of education and friendship:

A camaraderie grounded in a love of truth that awakens a person’s genius.

Tolkien and Lewis reshaped the literary world and the imagination of modern man, but their brilliance was cultivated in community.

Our enduring love for their work testifies to the power of virtuous friendship — how a small group of rightly ordered souls can shape history far beyond their own time.

If you want to continue their legacy, the best way is not only to love truth but to pursue it earnestly within a circle of virtuous, like-minded companions.

(By the way, I’m giving a talk on how to build such a community tonight. Details here)

May we all strive for the heights — with a few virtuous friends at our side — and deign to change the world.

Reminder:

Don’t miss this opportunity to participate in a live discussion TONIGHT about reclaiming the education modernity abandoned. Seats are limited — claim your spot here:

Imagine being a part of this club, i like to think such great quotes from Tolkien in LOTR were born in those sessions.

‘War must be, while we defend our lives against a destroyer who would devour all; but I do not love the bright sword for its sharpness, nor the arrow for its swiftness, nor the warrior for his glory. I love only that which they defend…’ Faramir

I think it was Lewis who’d said “live near your friends” — perhaps in his “Letters to Children”, or maybe it was “The Four Loves”?

I watched “Lewis & Tolkien” in the Museum of the Bible over Thanksgiving and learned two things for the first time:

1) there was a strain/estrangement between them when Lewis married Joy Davidman. Tolkien’s perspective was that marrying her as a divorcée, made an adulteress out of her. Lewis (per the play) was very hurt.

2) that while Lewis was a big encouragement for, and maybe inspiration of, Tolkien’s LOTR, Tolkien looked down his nose at Lewis’s world-building (or maybe lack thereof, in Tolkien’s mind)