The Mythic Trial That Built The West

Justice, Vengeance, and the Birth of Civic Order in Ancient Athens

The Oresteia is one of the oldest and most valuable texts in Western civilization. Written 2,500 years ago by the Ancient Greek playwright Aeschylus, it helped shape humanity’s understanding of justice.

On the surface, it’s a tale of wrath and vengeance, but beneath the narrative lies a question that challenged the foundations of Greek society, namely:

What is justice?

Aeschylus confronts Greece’s archaic, honor-bound form of “eye for an eye” justice, and forces his audience to reconsider whether simple vengeance is a truly virtuous expression of justice. The trilogy became a defining narrative of Ancient Athens, and is a cornerstone of the political and philosophical thought of Western Civilization.

Here's The Oresteia’s famous tale of vengeance, its questions on justice, and Aeschylus’ insights on virtue, piety, and what makes a truly just society.

Reminder:

Subscribe to support my mission of restoring Truth, Beauty, Goodness, and God to the heart of the West!

To Kill Or Not To Kill

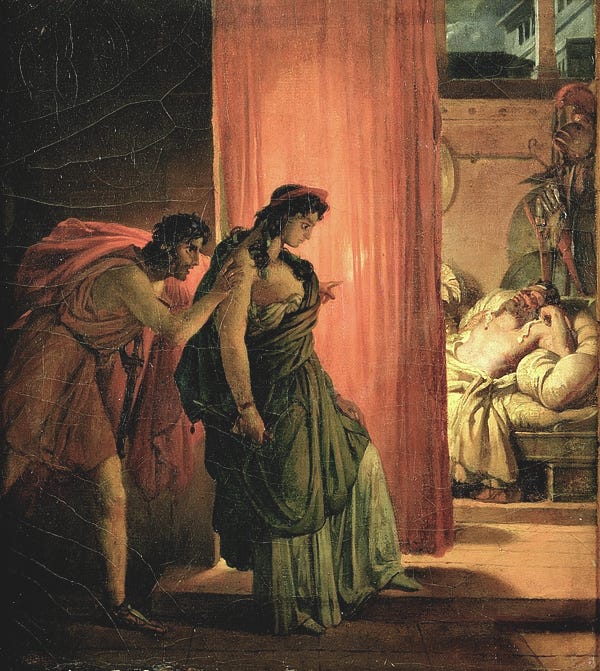

The Oresteia is a trilogy of plays — Agamemnon, Libation Bearers, and Eumenides. The first play follows King Agamemnon, returning home from the Trojan War. He’s then murdered by his wife, Clytemnestra.

Why?

Because Agamemnon sacrificed their daughter Iphigenia to the gods before the Trojan War.

Yet the key character to follow is not the deceased Agamemnon, nor Clytemnestra, but their son Orestes:

His father’s murder puts him in a difficult situation.

The Ancient Greek world handled murder similar to the ancient code of lex talionis, which said that if a man is murdered, his family must seek retribution.

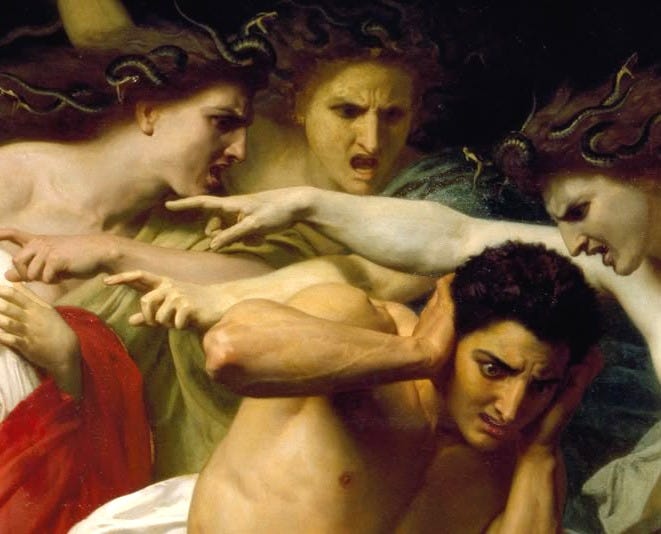

Unfortunately, the murderer was Orestes’ mother, which means that if he kills her, he violates the miasma, a doctrine that says you cannot murder your own blood. To do so incurs the wrath of the furies — primordial goddesses who hunt, torture, and torment violators of this law.

So Orestes is forced to choose between vengeance or non-vengeance. It’s an inescapable situation that puts the entire ancient Greek system of justice into question. He’ll either shame the gods via inaction, or incur the wrath of the furies if he murders his mother.

How can he escape, and more importantly, what is the just course of action?

The god Apollo will arrive to guide us.

Piety and Vengeance

Apollo commands Orestes to kill Clytemnestra, insisting vengeance must be upheld.

Orestes knows this will incur the Furies’ wrath, but he dares not ignore the Olympian gods. He kills Clytemnestra, and this matricide stains his soul — the Furies emerge from the underworld to torment him.

If the play ended here, the story would be tragic, but still brilliant.

Why?

Because even this portrait of revenge killing reveals a truth of natural law.

Orestes’ fate would be that of a man in perpetual flight — hounded without end, unable to rest without anguish. His plight recalls the mark of Cain, condemned to wander after killing Abel.

The ethic is clear: lex talionis — mere vengeance — is an insufficient form of justice. Orestes’ suffering mirrors that of the vigilante who takes justice into his own hands. He’s become the proverbial, “wicked man that fleeth when none pursueth.”

Aeschylus hints that if justice is to prevail, it must go beyond lex talionis — it cannot be administered by a single, biased individual.

So the question remains — how will Orestes escape the Furies? And what is the right way to administer justice after his matricide?

Aeschylus’ conclusion not only resolves Orestes’ plight, but matures a dialogue that has shaped 2,500 years of Western thought on justice and goodness. The solution involves a mythic trial overseen by Pallas Athena herself.

And so, hunted by the Furies and condemned by the old laws, Orestes stands trial before the goddess of wisdom — a trial that will decide not only his fate, but the very meaning of justice for all time.