How Geniuses Studied History

And why Modern Education Produces Historical Illiteracy

I’ve long lamented the tragic state of modernity, which has hollowed out the core of a classical education once capable of forming the soul in virtue.

The great books and thinkers of antiquity matter because they offer received wisdom— truths that train the mind to conform to reality. This is the foundation of any worthwhile education, and it gives real meaning to the claim that truth sets us free, and that human flourishing comes from acting in accordance with virtue.

While I often praise philosophy, theology, and great fiction, it would be a serious omission to neglect history. In the classical world, history was among the surest ways to form great-souled men—men shaped not only by practical wisdom, but by the courage to defend the True, the Good, and the Beautiful.

Today, however, the study of history has been reduced to a husk of its former self. In what follows, I’ll explain why modern historical education fails, how the classical approach can be recovered, and how doing so can teach us to see the world as the heroes of antiquity once did.

Reminder:

Subscribe, if you’d like to support my mission of restoring Truth, Beauty, and Goodness to the West, subscribe below!

Paid members get an additional members-only email each week!

The Problem of Positivism

The problem with today’s study of history is it’s been influenced by historical positivism — a practice in which historians pursue objectivity of the past by only sharing the “cold hard facts,” without any personal interpretation.

This is admirable in theory, to pursue objectivity, because it assumes that any proper appraisal of history ought to consider all the relevant points of influence in any story, which will allow readers to make their own informed judgments.

However, the issue is that it’s impossible to get a purely “objective,” understanding of history. In any given narrative or historical occurrence, even a positivist historian still must subjectively choosewhich facts to include or exclude. History can never be told without human bias.

Yet this isn’t even the biggest shortcoming of positivism. Even if you could give an objective, unbiased account of history solely based on the facts, such an effort would gut the true meaning and purpose that informed all classical historical study throughout antiquity.

The Classical Mode

Historically, the study of history was not primarily concerned with objective, value-neutral accounts of the past. It was pursued with a clear purpose, namely, the formation of the soul in accordance with virtue and wisdom.

This is most clearly seen in Plutarch, best known for Parallel Lives. The work contains forty-eight biographies of great-souled men from Greek and Roman antiquity. If you read this work attentively, it offers you a substantial understanding of Greco-Roman history through the lives of its most influential figures.

But the true value of Plutarch’s Lives lies beyond factual knowledge.

Plutarch himself explains his aim:

“My design is not to write histories, but lives. And the most glorious exploits do not always furnish us with the clearest discoveries of virtue or vice in men; sometimes a matter of less moment—an expression or a jest—reveals character more clearly than the greatest sieges…

As portrait painters attend most carefully to the features in which character is seen, so I must be allowed to focus on the marks and indications of the soul.”

Plutarch’s biographies were morally charged. He did not reject facts, nor make fabrications, but he subordinated historical narrative to moral intelligibility. He did so by emphasizing select incidents that revealed virtue, vice, and character traits of these figures, rather than merely recording events with a neutral, scientific manner.

The structure of Parallel Lives reflects this aim. The biographies are arranged in twenty-four paired lives, one Greek and one Roman, explicitly compared and evaluated with each other. For instance, Alexander the Great is set beside Julius Caesar; after narrating their lives, Plutarch weighs their virtues and their failings.

Through reading Plutarch, you discover history is not merely a record of events but an education in human nature. You learn how great men rose to power, navigated politics and war, endured betrayal and exile, and responded to fortune and misfortune alike.

For Plutarch, true history was not the study of past events in isolation, but a moral narrative ordered toward the formation of the soul… yet Plutarch’s wisdom goes even further than development of character.

Plutarch’s classical mode of historical understanding offers an entirely new wisdom, absent from the modern, positivist approach to education.

Carthago Delenda Est

What kind of wisdom does the classical understanding of history actually impart?

G. K. Chesterton addresses this directly in The Everlasting Man, using the Punic Wars as his example. He makes a simple but jarring claim:

You cannot truly understand great historical events, especially decisive ones, without the classical mode of historiography.

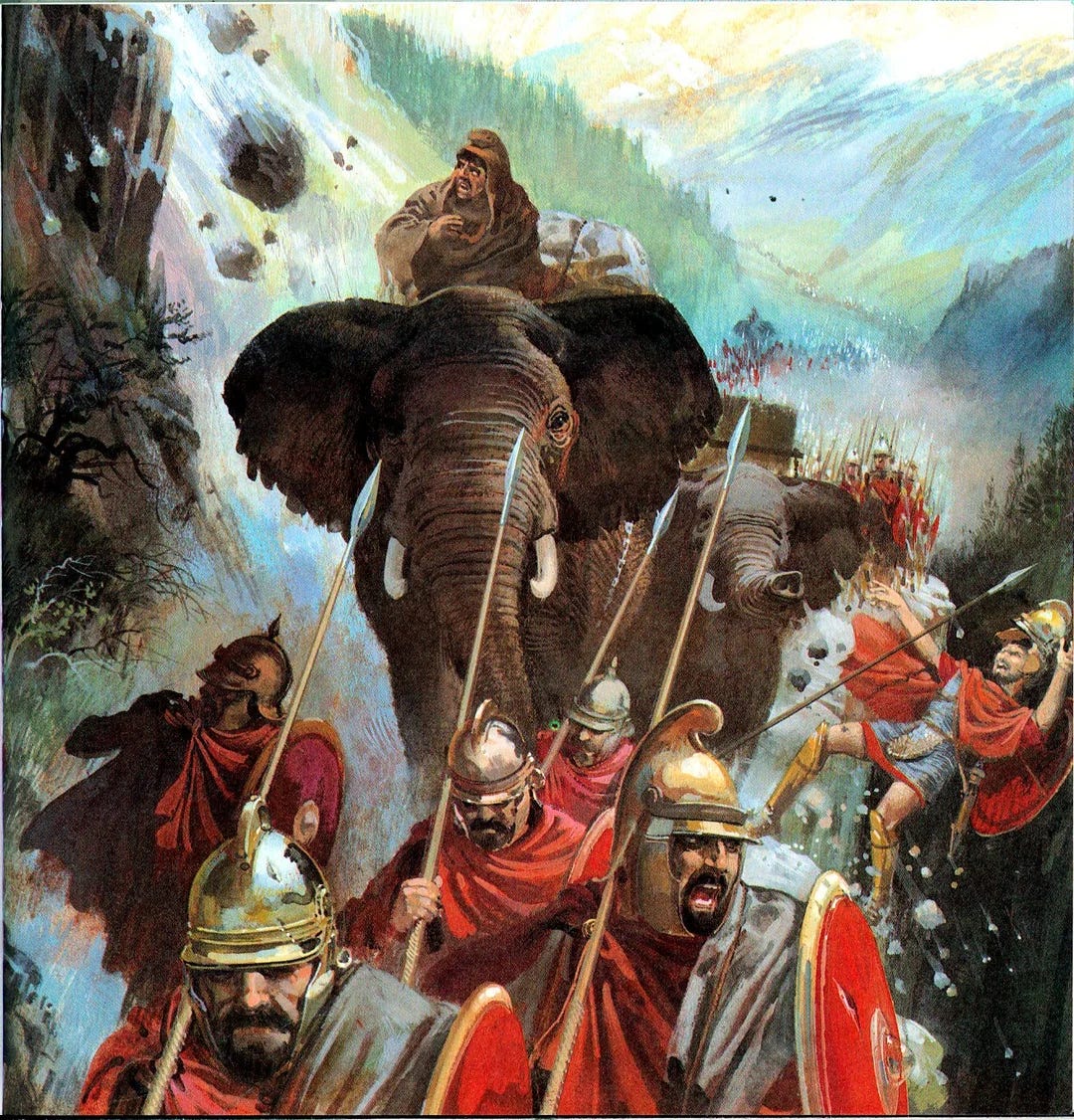

As a brief reminder, the Punic Wars were fought between Rome and Carthage. Hannibal famously led his elephants over the Alps, devastating the Roman countryside, crippling Rome’s economy, and killing hundreds of thousands. By any rational calculation, Rome should have surrendered. Carthage fully expected her to.

…and yet Rome did not.

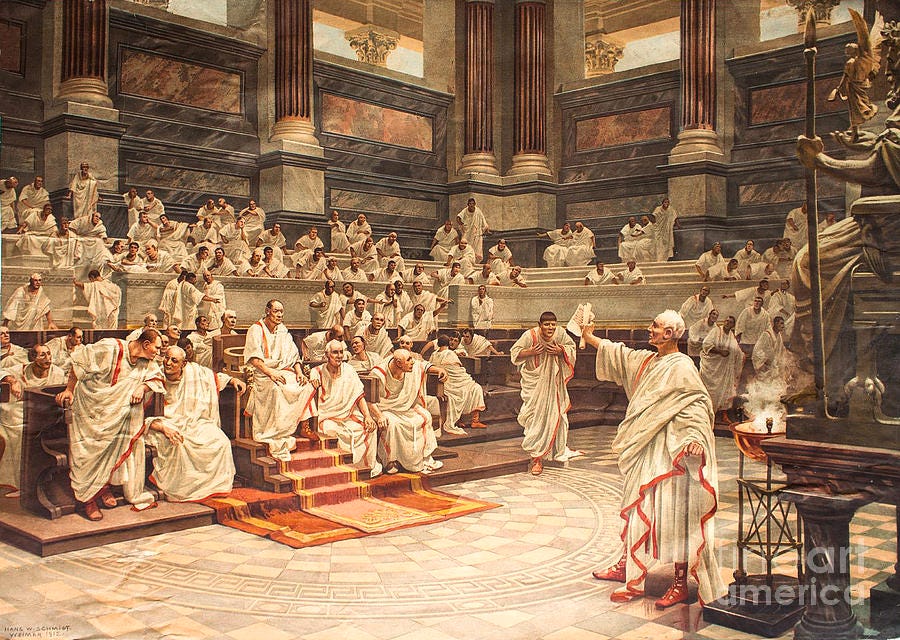

“Carthago delenda est!” Cato the Elder repeatedly thundered in the Roman Senate, “Carthage must be destroyed!”

Against every expectation, Rome recovered. Under leaders like Scipio Africanus, she launched a renewed campaign and ultimately broke Carthage’s power.

Chesterton argues that no accumulation of historical facts can adequately explain this reversal. A nation in ruins, facing one of the greatest generals in history, on the brink of annihilation, does not simply rebound by logistics or strategy alone. The explanation, Chesterton insists, is moral:

“Men did not love Rome because she was great. Rather, Rome was great because men loved her.”

For all her flaws, Rome possessed a moral seriousness that was rare in antiquity. She prized duty, law, discipline, and self-sacrifice for the common good. Just as importantly, she despised Carthage — not merely as a rival empire, but as a commercial power infamous for corruption and child-sacrifice to Moloch.

The point is this: Rome’s greatest victory cannot be understood through facts alone. Rome was not an abstraction; she was a people. A proud people, animated by an austere moral vision, a fierce devotion to duty, and a revulsion toward cultures that sacrificed the innocent.

Rome’s war was not simply about territory or power. It was a moral conflict, a story of good and evil, that enabled a battered people, in their darkest hour, to rise again and defeat a seemingly unstoppable empire.

Conclusion

If you’re to read Plutarch’s Lives, and study the great events of history as moral narrative for formation of soul, you’re to give yourself the education of the greatest statesmen, generals, leaders, and politicians throughout history.

You’re to give yourself a masterclass in learning practical wisdom and the hearts of man. You’re going to learn not just the great events of history, but the hearts and souls of mankind’s greatest heroes and villains. You’re to learn not just how to wrestle with fate, nor even build your own empire, but also how to recover when fortune deals you a fickle and cruel blow.

A true understanding of history can never be grasped devoid of its humanity, it’s morality, it’s story. Nietzsche himself agreed:

“Fill your souls with Plutarch, and dare to believe in yourselves when you have faith in his heroes. With a hundred people raised in such an unmodern way, that is, people who have become mature and familiar with the heroic, one could permanently silence the entire noisy pseudo-education of this age.”

Indeed, it may be as small a number as 100 virtuous souls to change the world. If you read Plutarch, and dare to count yourself amongst that 100, you may be rightly assured this world will find itself a place for the better.

Reminder:

Subscribe, if you’d like to support my mission of restoring Truth, Beauty, and Goodness to the West, subscribe below!

Paid members get an additional members-only email each week!

I'm much too old, sick, age 77, to have any hope of doing much with Plutarch's Lives, but the interest is here. Earlier I could have realistically aspired to do so.

What 3 or 4 would you recommend?

I'm a early retired internist general internist making myself useful in unaffiliated community development, sometimes medically related, here in Honduras xv25 years. Single pat of 3 generational family.

We are both are too complex to even WANT to be clones of anyone, but I love to hear you think. Intellectually loneliness, only partially assuage bt many self directed studies X 50 YEARS.

I don't have a reading buddy. Mine are long passed away

Thanks for writing this, Sean!

One part that really stood out to me was, "Plutarch’s biographies were morally charged. He did not reject facts, nor make fabrications, but he subordinated historical narrative to moral intelligibility."

I've been thinking for many years about the purpose of history. I, too, was trained to aspire for objectivity, while acknowledging that I would inevitably have bias (but this seen as a generally negative thing). This wasn't very satisfying to me, since I found it difficult to explain why I would do history at all, in that case, apart from pure personal enjoyment and interest.

When I became a Christian, though, this didn't make sense to me. Yes, I wanted to get as close as possible to the facts of the matter, and sometimes bias can get in the way, but as you pointed out, Sean, history is not meant to be pursued for "the facts" alone. History must be morally intelligible. It must be "ordered toward the formation of the soul." Great stuff!