Why Odysseus Rejected Immortality

And the Curse of a Life without Death

Imagine you’re a fierce, hot-blooded Ancient Greek warrior. You’re a 10-year veteran of the Trojan War, and you will spend the next 10 years on a return voyage from hell.

On the way, you’ve fought sea beasts, cyclopes, witches, and the wrath of the Olympian gods. All your crew members are dead. You’re shipwrecked, starving, and taken captive by an immortal nymph.

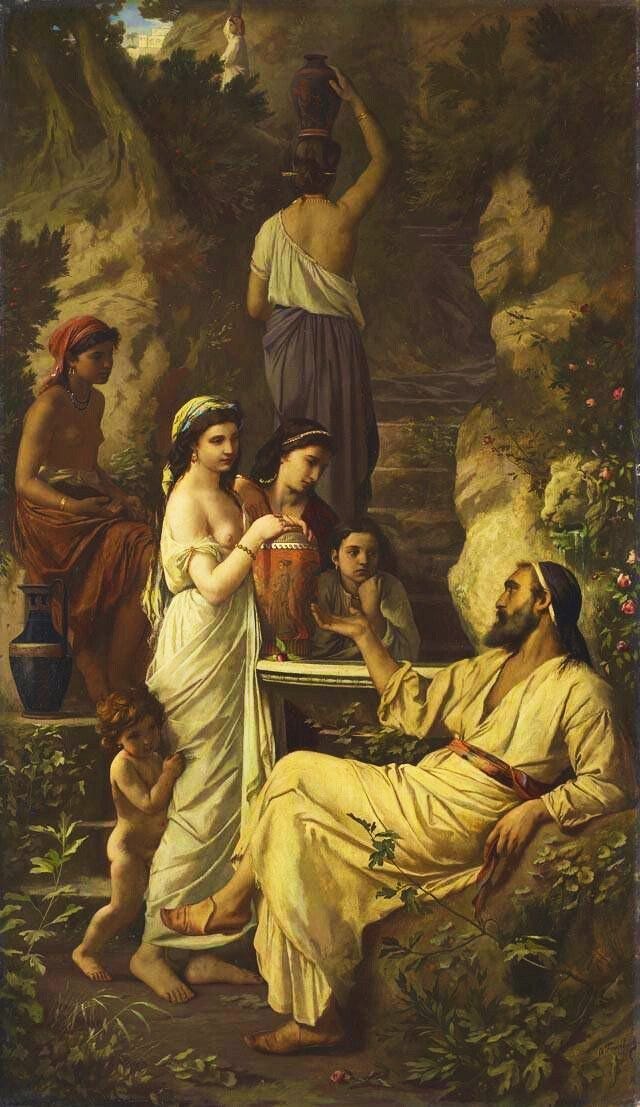

Such was the plight of Odysseus when he was detained by the goddess Calypso.

She forced him to become her lover, then offered him the opportunity of a lifetime:

Immortality.

To state it plainly, Odysseus was offered eternal youth, sex, and pleasure on Calypso’s island, free from suffering.

The alternative?

Return to the sea, endure more suffering, and hope to reach home before dying.

This is perhaps the most famous ultimatum in Greek mythology, and Odysseus proves himself the cleverest of Greek heroes in his response. Here’s how he answers the offer of eternal life, and what it teaches you about the human condition.

Reminder:

Subscribe, if you’d like to support my mission of restoring Truth, Beauty, and Goodness to the West, subscribe below!

Paid members get an additional members-only email each week!

Teary-eyed and Broken

Odysseus’ introduction is jarring. We remember him as the mastermind of the Trojan Horse, and expect to find a great-souled hero.

Instead, we find him weeping on a beach.

Homer writes:

“Calypso found Odysseus sitting upon the beach with his eyes ever filled with tears, and dying of sheer home sickness; for he had got tired of Calypso, and though he was forced to sleep with her in the cave by night, it was she, not he, that would have it so.

As for the day time, he spent it on the rocks and on the sea shore, weeping, crying aloud for his despair, and always looking out upon the sea.”

For seven years, Odysseus has lived in utopian pleasure with the beautiful goddess Calypso. His desires are satisfied, and he is safe from Poseidon’s wrath… and yet he is devastated.

He longs for home and his family.

Zeus decrees he must be released. Calypso relents, but offers one final temptation before he leaves.

The Offer of a Lifetime

Calypso says:

“Odysseus, noble son of Laertes, so you would start home to your own land at once?

Good luck go with you, but if you could only know how much suffering is in store for you before you get back to your own country, you would stay where you are, keep house along with me, and let me make you immortal,

no matter how anxious you may be to see this wife of yours, of whom you are thinking all the time day after day;

yet I flatter myself that I am no whit less tall or well-looking than she is, for it is not to be expected that a mortal woman should compare in beauty with an immortal.”

Odysseus must be tactful here. To offend the gods is a capital offense that risks death — as Poseidon has always proven.

Odysseus’ response:

“Do not be angry with me about this. I am quite aware that my wife Penelope is nothing like so tall or so beautiful as yourself. She is only a woman, whereas you are an immortal.

Nevertheless, I want to get home, and can think of nothing else. If some god wrecks me when I am on the sea, I will bear it and make the best of it. I have had infinite trouble both by land and sea already, so let this go with the rest.’”

Odysseus affirms Calypso’s beauty and virtue, but insists on returning home, even though it promises suffering, pain, and death.

In short, he values a short, suffering-filled life, over an everlasting life of pleasure.

Why would he turn down Heaven on Earth?

Yes, he misses his family, but there’s a deeper layer.

Odysseus discovered something worth dying for — and in doing so, revealed that the meaning of life is grounded in something greater than mere self-preservation.

From that realization emerged a truth that has become one of the bedrock principles of Western civilization: a good and meaningful life is found not in clinging to existence alone, but in orienting oneself toward that which is worth sacrifice.

The Curse of Immortality

How does this revelation play out in the narrative?

We must recognize Odysseus was not just homesick for his family. His wife and kid are going to die, and Odysseus too, shall die. And there’s no hope for a good life after death.

The emphasis is not that Odysseus chooses his family, but that he rejects immortality itself.

Odysseus recognized the ancient wisdom that immortality is a curse for mortal man.

How can we know?

Homer gives us a hint at the beginning of the chapter:

“And now, as Dawn rose from her couch beside Tithonus—harbinger of light alike to mortals and immortals…”

Homer evokes the myth of Dawn and Tithonus. In this myth, Tithonus was granted immortal life but not immortal youth. He aged endlessly and shriveled to a husk.

The same thing is happening to Odysseus in real time!

Even if Odysseus was granted eternal youth, his soul would still shrivel all the same… and as such, Odysseus recognized that man was not made for immortal life.

The paradox is, Odysseus found life by choosing death, because the dangers of the high seas restored adventure, virtue, and meaning to his soul.

Life then, is not about endless pleasure, or an end to suffering, but a perseverance in virtue over suffering. Such a life leads to adventure… an adventure that bears life to your soul, and leads you to a true and natural mortality… a mortality which affirms the grandeur of life itself.

Homer reveals all in the story’s conclusion.

A True Immortality

Odysseus does make it home. He endures many more trials and tribulations, and suffers immensely.

This is evoked in Odysseus’s very name, which loosely translates as “he who suffers much.”

We see that the man who suffers greatly, in the name of virtue, leads a meaningful life. And we see a natural answer to immortality when he reunites with his son, Telemachus.

Together, the father and son return order and justice to their home and kingdom. Telemachus grows in virtue, and becomes the noble successor to Odysseus. He shall rule wisely ever after, and the kingdom of Ithaca shall prosper.

As such, true immortality lies within posterity, and the virtue one passes down to the next generation.

Man was not made for endless pleasure, nor was he made to live forever. He was made to live meaningfully, nobly, and virtuously within time:

He who lives briefly but well, lives better than he who has been granted endless days in mindless pleasure.

Such is Homer’s enduring insight — a theme that has since sounded off through 2,500 years of Western storytelling, and man’s search for meaning.

Reminder:

Subscribe, if you’d like to support my mission of restoring Truth, Beauty, and Goodness to the West, subscribe below!

Paid members get an additional members-only email each week!

Homer…. Epic

People do not understand how important God as a person must be to make eternal life desirable.

I witnessed a presentation on Middle Earth and the presentation of the Gospel into the Greek Speaking world of the first century.

Given by the head of the The Torrey Honors Institute at BIOLA University.

The thrust was Odysseus crying (the first man of tears in literature) on the shores of adult Disneyland, living with a Goddess. He knew the Goddess would go on her period and lash out, eternally. Being eternal with her was no blessing.

He longed for Penelope, his wife.

Then they met Hercules in hell, who said it was better to be a sheep herder in middle earth than a jibbering shade in hades.

In the Greek world Heaven was not a place for men because the Gods were a terror to live with. Nor was hell a place for men.

They were caught hanging between heaven and hell,

in MIDDLE EARTH 🌍.

Then the God whose character was worth living with, Jesus. Was presented to that world.

The True, The Good, and the Beautiful.