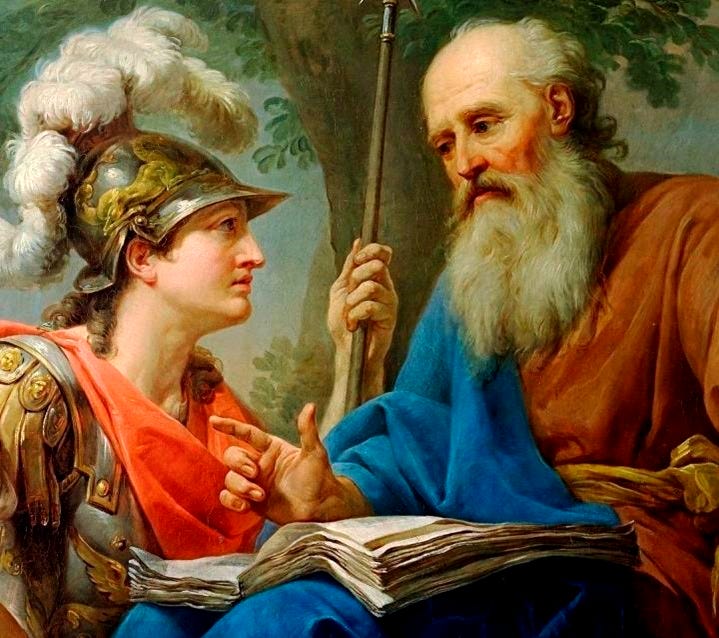

Why Plato Loved Censorship (Yes, Really)

Analyzing the Most Controversial Idea of The Republic

Plato is widely regarded as the most influential philosopher in human history, and The Republic his magnum opus. The work asks “what is justice?” and is often considered the greatest piece of political philosophy ever written.

Yet it’s in this very masterpiece that Plato presents some of his most uncomfortable and controversial ideas. And of these, the most controversial is this:

Plato believed in censorship of the arts.

When outlining his ideal, utopian state, Plato says censorship of books, music, and artwork is mandatory not only for a flourishing civilization, but to ensure that its citizens live virtuous, meaningful lives. To this day, scholars are divided on whether this idea was genius, or the first outlines of authoritarian thinking.

Today we’ll explore his argument, and what it can teach us about Plato’s vision, his genius, and what it truly takes to build a civilization of philosopher kings.

Reminder:

Subscribe, if you’d like to support my mission of restoring Truth, Beauty, and Goodness to the West, subscribe below!

Paid members get an additional members-only email each week!

Is Justice Actually Good?

Plato’s calls for censorship appear in Book 2 of The Republic. For context, the book begins with two interlocutors — Glaucon and Adeimantus — challenging Socrates to prove that justice is good for the soul.

They even steel-man the opposing view, which can be paraphrased as such:

“Socrates, imagine one man is publicly ‘just,’ loved by all, but secretly unjust, becoming wealthy and powerful through injustice.

Now imagine another is publicly mocked and poor, but always just and honest, even though he is hated. Prove to us that it is STILL better to be just, even then.”

In other words, Socrates must prove that justice is not merely a means for law and social cohesion, but is truly a virtue that benefits the soul.

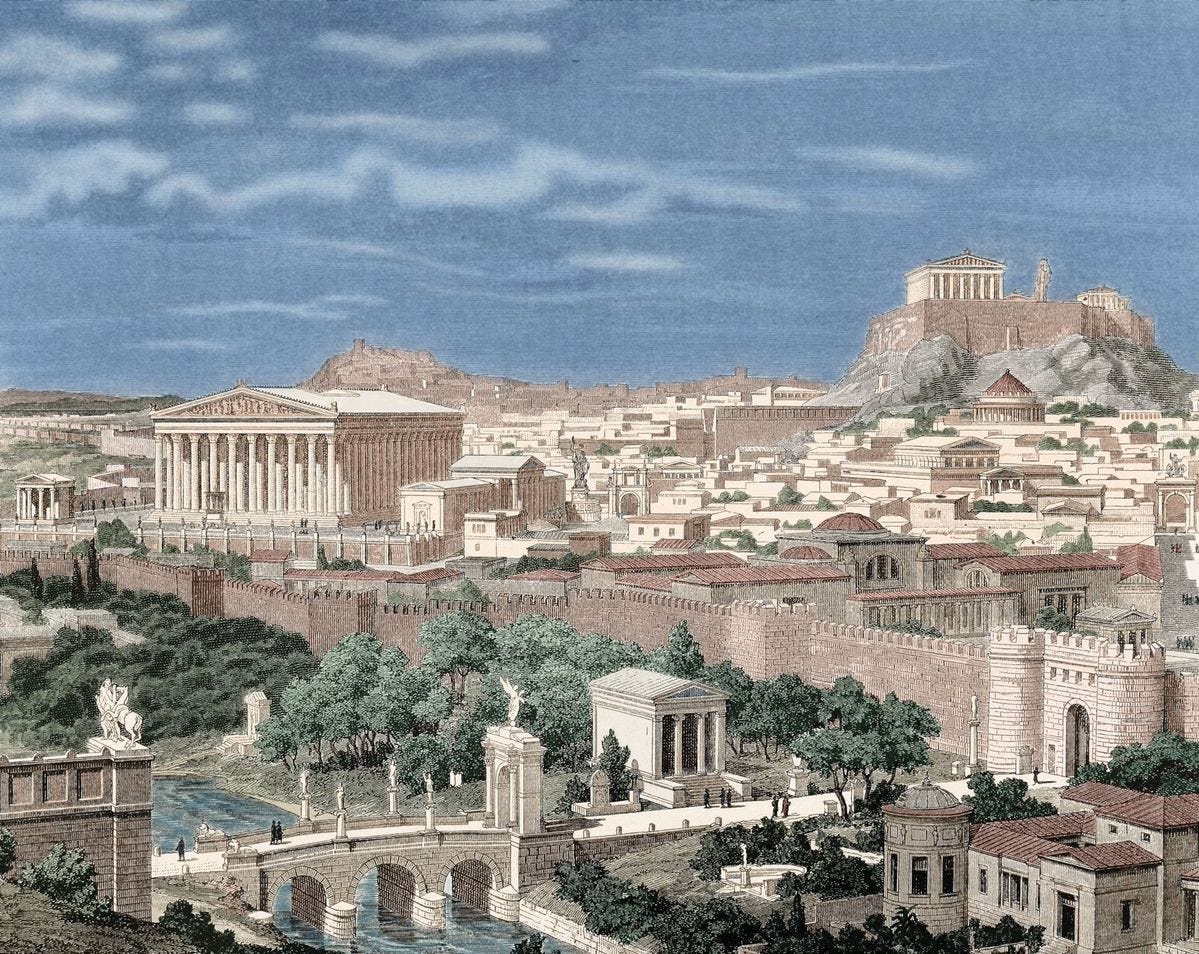

He accepts the challenge, but says that to demonstrate it, we should first examine the health of a city, or a community of thousands of souls, because justice and injustice are easier to see at scale.

The City is a Map of the Soul

Socrates argues that a city has a “soul” just like an individual. A healthy city is made of healthy souls working in harmony; a sick city is composed of disordered, vicious souls in conflict.

So a good city requires harmony grounded in virtue, and this harmony must be established through education.

Education, for Plato, is not about accumulating information. It is about forming souls to love virtue.

At the time, Greek education meant poetry, especially Homer, but Socrates infamously disliked Homer. He lamented that Homer was a talented artist, but observed his tales are not morally edifying. Its heroes are dubious, violent, and perhaps even villainous.

Therefore, Socrates fears such poetry would corrupt the youth, so he calls for censorship:

“We must first supervise the storytellers. We will select their stories whenever they are fine and beautiful and reject them when they are not… Many of the stories we tell now must be thrown out, especially those that Homer, Hesiod, and other poets tell us, for they compose false stories.”

While censorship sounds authoritarian, notice that Plato is doing something subtly brilliant. He does NOT think education is about vain accumulation of knowledge, rather it’s about formation of the soul. Specifically, he asserts that a soul must be trained to love Truth, Beauty, and Goodness, even before fully understanding them. True education is about the heart.

So Plato insists that not all knowledge is good knowledge, and not all poems or books are good education.

As moderns today, we usually associate censorship with tyrants — the authoritarian few who manipulate truth or spread propaganda so they can maintain power. Notice, however, that Plato is not at all concerned with gaining power (in fact, he’ll later say that the ruling class should have NO property, wealth, or luxuries).

For Plato, censorship had nothing to do with power for its own sake, and everything to do with virtue. Immoral and wicked ideas SHOULD be censored, he says, because they corrupt souls, especially amongst children.

Still, a key problem remains:

Who decides what gets censored? Who determines what is good? How can censorship avoid becoming a tool of the powerful?

Plato DOES have a response to these objections. While the fullness of his argument remains controversial, he does share one key idea that revolutionized mankind’s entire idea of education.

It’s the same idea that got Socrates sentenced to death; yet this idea lived on and has since molded education to this day, 2,500 years later.