Why Misfortune is Good for your Soul

According to Great Philosophers

In order to live a good life, you must understand man’s relationship to fortune.

The very beginning of the Western literary tradition — based upon Homer and the Greek tragedians — began by lamenting the human condition, that we suffer beneath the twists and cruelties of fate itself.

Their thinking was clear:

Ignore fortune at your peril, for ruin will be sure to follow… but if you have a proper understanding of fortune then it can minimize suffering and even guide you to prosperity.

This line of thinking didn’t just inspire Ancient Greece, but began a longstanding tradition of philosophical inquiry over the nature of fortune throughout antiquity, medieval Christianity, and even into the modern Renaissance.

Every age agrees — the good life requires a proper understanding and relationship to fortune.

Today, we’ll look at three great philosophers’ understandings of how fortune works, how man ought to respond to it, and how it can help you live well.

Reminder:

Subscribe, if you’d like to support my mission of restoring Truth, Beauty, and Goodness to the West, subscribe below!

Paid members get an additional members-only email each week!

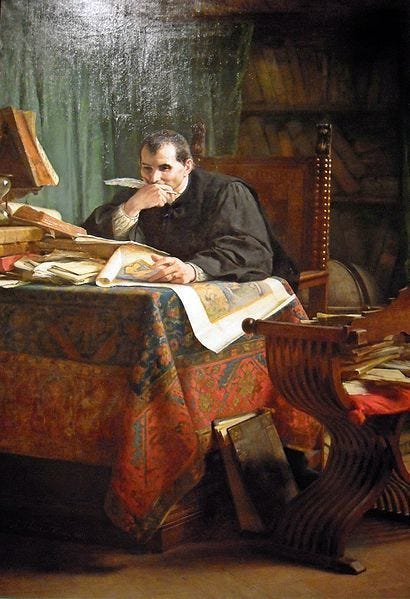

Strike Fortune Down

500 years ago, Machiavelli wrote literature’s most controversial writings on fortune in his landmark book The Prince. This work argues that two forces govern all life:

Virtu and fortune.

Virtu is roughly defined as force, or effectiveness at achieving one’s ends. Machiavelli says the ideal prince is rich in virtu, and is therefore a master at gaining and securing power (by any means necessary). However, virtu is just half the equation.

Machiavelli says fortune, or chance, governs the other 50% of a prince’s life. This is not good, in Machiavelli’s eyes, for fortune can pose a threat to a prince losing his power.

Machiavelli offers a blunt and jarring prescription to handle the fickleness of fortune:

“It is better to be impetuous than cautious, because fortune is a woman; and it is necessary, if one wants to hold her down, to beat her and strike her down…

She lets herself be won more by the impetuous than by those who proceed coldly. And so always, like a woman, she is the friend of the young, because they are less cautious, more ferocious, and command her with more audacity.”

Machiavelli urges the prince to “make his own luck,” through decisive, swift action, which is often violent when necessity demands it. As fortune is something to be dominated, so the prince must be willing to act against social bonds, moral norms, and even mercy itself in order to secure virtu.

I’d posit such a philosophy may make you powerful, but not happy, and certainly not morally virtuous as the classical philosophic tradition exhorts you to be.

Whereas Machiavelli says you’re to be an empowered prince, the greatest thinkers before him suggested you’re to be a generous and just soul, even if fortune’s fickleness points you towards death itself.

And few better argued this point in the face of maximum misfortune than Boethius.

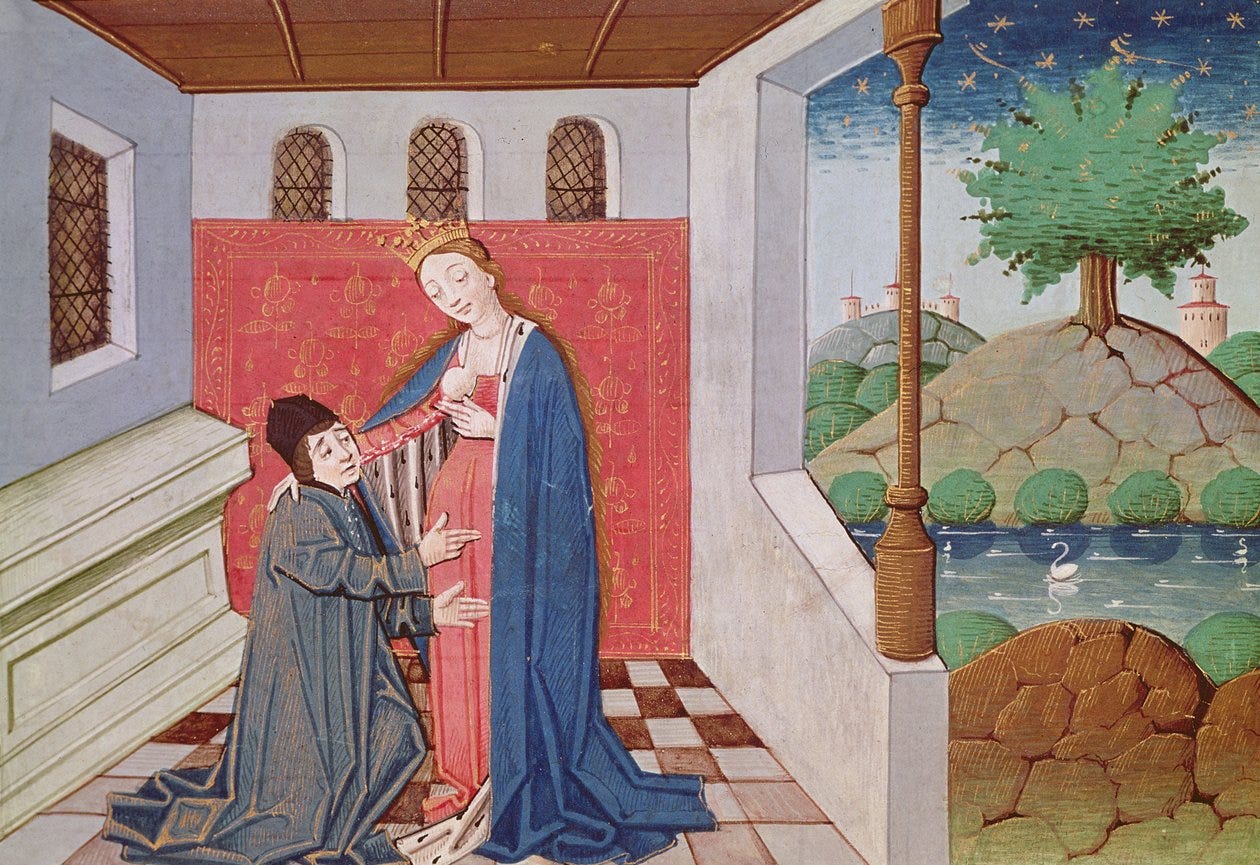

Lady Fortuna

Boethius was a Roman Politician who spent his life trying to revive classical education in the crumbling empire, hoping a unity of virtue could save its people. Instead, he found himself arrested on false charges, imprisoned, and sentenced to death.

In the final days of his jail cell, he writes his masterpiece — The Consolation of Philosophy — in which he turns to Lady Philosophy to console him in the face of death. In this work, the personified Lady Philosophy admonishes his grief over his fortune’s fickleness, and teaches him this brilliant insight:

“All fortune is good fortune; for it either rewards, disciplines, amends, or punishes, and so is either useful or just.”

Boethius says fortune is not a woman to strike, rather she is a revealer of false goods and a teacher of detachment. Fortune’s ultimate insight to Boethius, in the face of death, is simply: “if something can be taken from you, then it was never truly yours.”

You own nothing in this life but your soul, and so put your faith in philosophy to make you virtuous. To do so, as Boethius himself proves, is to live so well that not even death, torture, and worldly privation can harm you…

Yet these are more than words of false assurances. For one, The Consolation of Philosophy shows that misfortune seems to have genuinely led Boethius to contemplation, wisdom and true solace… and yet that’s not even the end of Boethius’ story.

After he dies, his work gets discovered posthumously, and Consolation of Philosophy has since gone on to become a staple of classical education for 1,000+ years in counting. Boethius may have failed to save Rome in his lifetime, but it was his noble handling of misfortune that ironically, led him to save, bolster, and inspire the entirety of Western Civilization thereafter.

And finally, we arrive at what I would posit to be the last and most nuanced view of fortune.

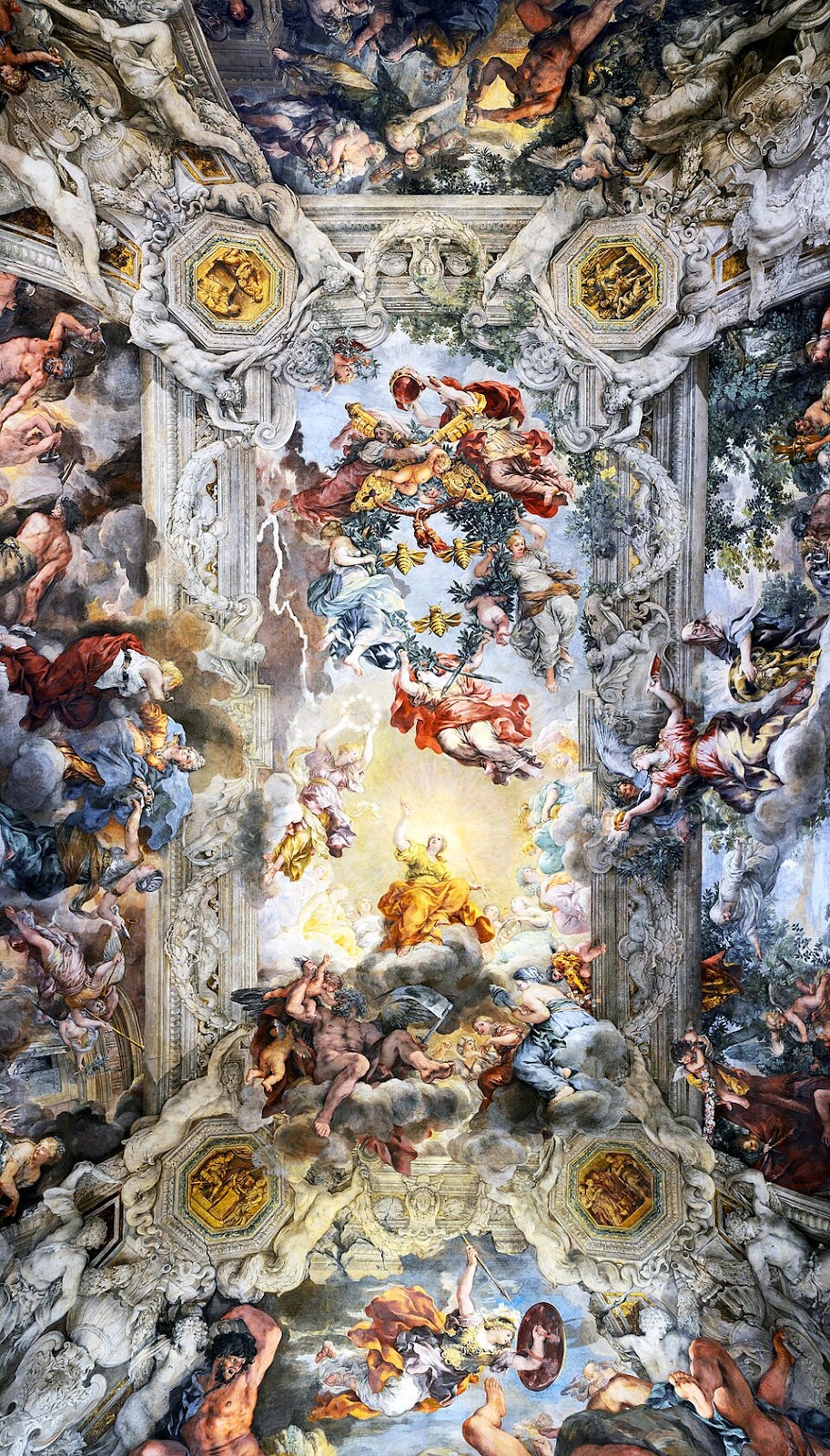

Fortuna and Inferno

Dante Alighieri famously personified Lady Fortuna in his poem the Inferno. She appears in the 7th canto as a “general minister and guide,” of God, who oversees the movements of wealth throughout Earth.

Of Lady Fortuna, Dante writes:

“Your wisdom cannot withstand her: she foresees, judges, and pursues her reign, as theirs the other gods. Her changes know no truce. Necessity compels her to be swift, so fast do men come to their turns.

This is she who is much reviled even by those who ought to praise her, but do wrongfully blame her and defame her. But she is blest and does not hear it. Happy with the other primal creatures she turns her sphere and rejoices in her bliss”

So Lady Fortuna is not just a teacher, as Boethius suggests, but a being who, properly understood, disposes the soul to charity by stripping away false worldly attachments.

Dante elevates Fortune from a mere teacher to an instrument of Providence itself: an administrator within a divinely ordered cosmos.

The reminder is not just “remember to care for your soul,” but now includes, “remember that Goodness governs existence.” What Dante suggests is, the end goal of misfortune is more than philosophy (self-knowledge) but charity — a love of God, man, and being itself.

Dante sets a high bar for us — perhaps one we cannot attain, for who can abide in perfect charity amongst life’s many misfortunes…?

Yet an unreachable ideal does make it worthless. In fact, it’s these precise ideals that make man virtuous virtuous: good fortune encourages generosity, piety, and gifts to God and man, and misfortune encourages humility, wisdom, and dependence upon God.

Though man remains forever imperfect, fortune handled nobly makes him more perfect.

Modern Day Dantes

The siren-song of Machiavellianism has dominated the psyche of modern man. We are largely agnostic, concerned with “this world,” only, and believe we ought to “make our own luck.”

As such, the wealthy and influential are called blessed, the poor and disenfranchised cursed. It’s become a complete inversion of Plato’s virtue ethics — shirk wealth in love of virtue — and Christ’s exhortation that blessed are the meek.

As we can see, the Boethius/Dante arc of meditating on fortune proves to point to charity:

Learning to love “love,” itself. As Dante puts it, learn to love the “love that moves the sun and stars.

This notion is not only the culmination of The Divine Comedy, but a bedrock conviction of the classical–Christian moral tradition.… Charity in all things, for without it, even all other gifts become vanity.

Fortune, then, is not an enemy to be beaten, coerced, or cursed at… she’s actually a veil meant to be pierced. Both her gifts and her deprivations train the soul to love what cannot be taken away.

Those who learn this discover a freedom no prince can secure and no misfortune can destroy. For those who do, they may discover this very love we’ve meditated upon, what awaits is an assurance of wisdom that conquers all temptations of good fortune, and all sorrows of misfortune.

Reminder:

Subscribe, if you’d like to support my mission of restoring Truth, Beauty, and Goodness to the West, subscribe below!

Paid members get an additional members-only email each week!

Good stuff.

"Yet an unreachable ideal does make it worthless."

Perhaps you meant "doesn't".

Excellent as always.